|

One of the original Early

Birds (image of him at this link), William S. "Billy"

Brock landed at the Davis-Monthan Airfield six times between

February 12, 1927 and February 22, 1929. His globe-circling

partner (see images and texts below), Ed Schlee, was his

passenger on October 4, 1928, when they landed in Bellanca J

NX7085. Please follow the airplane's link to learn more about the context of their October 4th landing at Tucson.

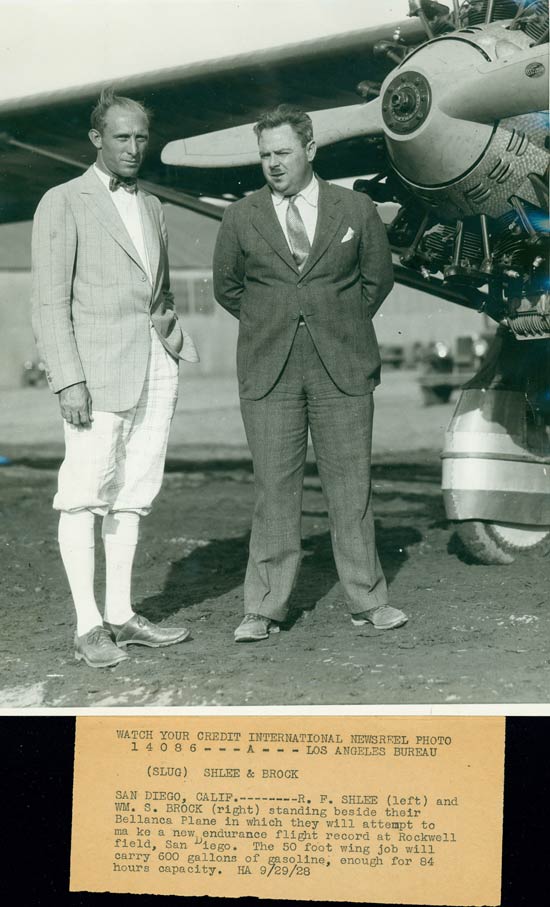

Ed Schlee (L) and Wm. Brock, September 28, 1928, San Diego, CA Standing in Front of a Bellanca Aircraft, Probably NX7085

(Source: Kalina)

|

Above, from Tim Kalina, an image of Schlee (L) and Brock taken September 28, 1928 in San Diego, CA. Mr. Kalina says of his image, "The Bellanca behind Schlee and Brock has to be NX7085, so in this photo we have a 'hat trick’, three D-M [Register] figures in one photo!" Below, from the Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University (WSU), is a photograph of Brock and Schlee dated November 2, 1928. Over a dozen images of them together and singly are at the link.

William Brock (L) and Edward Schliee, November 2, 1928 (Source: WSU)

|

Below, an undated image of Brock (L) and Schlee from their NASM biographical file.

Two landings, on February 12 and March 8, 1927, were in an

unidentified Stinson airplane. This aircraft could very well

have been the Detroiter SB-1, #3027 flown in the 1926 Ford Air Tour by Eddie Stinson. Via email, Brock's grandson confirms that it was. May people have contributed the photographs below over the years since this page went online in 2005. My thanks to all of them.

Site visitor M.H. from Kenilworth, England sent the image

below, from his father's collection, taken in Aden (now part of the Republic of Yemen)

in 1927 during the global flight. The Stinson SM-1, "Pride of Detroit",

and the registration number, NC857 (not a Register airplane), on the rudder, are nicely

exhibited. British military personnel crowd around, as well

as a small dog enjoying the shade under the wing.

Another three photographs immediately below, added September 12, 2014, are provided to us by R.D., another site visitor. R.D. states the photos were taken by his wife's great grandfather who was stationed in Iraq in the 1920s. The first image is identical to the one above, with a little less patina. Note the fuel or oil being poured into a tank by the man visible over the wing.

Stinson NC857, "Pride of Detroit," September 2, 1927 (Source: R.D.)

|

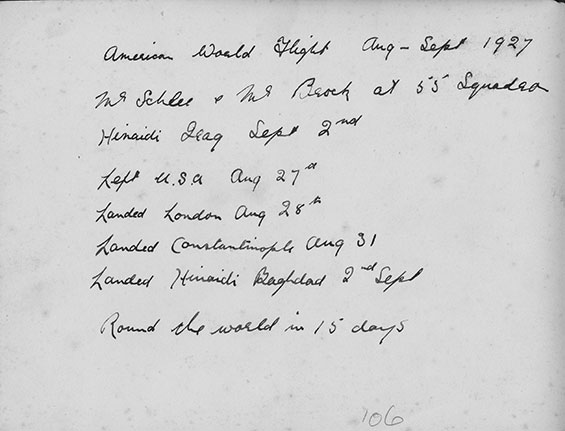

Below, the caption on the back of the photo above. It clearly documents key landings during the world flight of NC857, Schlee and Brock.

Stinson NC857, "Pride of Detroit," Caption, September 2, 1927 (Source: R.D.)

|

Below, an open air maintenance session is captured. It is not clear that this is the same session captured in the photograph next below.

Stinson NC857, "Pride of Detroit," Maintenance, September 2, 1927 (Source: R.D.)

|

Below is a similar photograph shared by site guest D. Hayman on October 4, 2019. She says about the image, "Attached please find the photo of "Pride of Detroit".... It was taken in 1927 by my Uncle William Tomlinson when he was with the RAF. He was also in attendance when Amy Johnson was flying from England to Australia and touched down in Jhansi India to refuel...." Compared to the photo above, the people standing around are in different positions, and there is a two-wheeled tail wheel support in the foreground. But, the two white cans visible in the foregound appear to be the same.

Stinson NC857, "Pride of Detroit," Maintenance, September, 1927 (?) (Source: Hayman)

|

Officially, Brock & Schlee's airplane is a Stinson M-2 Detroiter (not

SM-2, just M-2) serial number M-201, built June 20, 1927.

It had a Wright J-5 engine s/n 7556 and was described as a

6PCLM (6-place, Closed, Low-wing, Monoplane) when new. It was sold to Wayco Air Service, Inc., Detroit,

MI (E. F. Schlee, President) for "air taxi service".

Below, three photographs courtesy of site visitor Jackie Crabb. They were taken ca. Sep 6, 1927 when the "Pride of Detroit" was in Calcutta, India. She says about the photographs, "I recently delved into my grandparents photo albums and came across three pictures of Pride of Detroit plane. In 1927 my grandparents were living in Calcutta, India. My grandfather worked for Goodyear. In my research of the Pride of Detroit flight in 1927 I see that it landed in

Calcutta on September 6, 1927. My grandmother is in two of the pictures."

"Pride of Detroit," Calcutta, India, September 6, 1927 (Source: Crabb)

|

Contributor Crabb's grandmother is holding the parasol at left in the photo above. These three photographs were taken by her grandfather, John L. Nicholson.

"Pride of Detroit," Calcutta, India, September 6, 1927 (Source: Crabb)

|

The gentleman standing at right, above, appears to be Schlee, and on the box is probably Brock. Notice the canvas rollup tool kit on the ground by the wooden case. I can identify a hand grease gun, a wrench and the head of a ball peen hammer tucked in its pouch next to the grease gun. On the top of the wooden case appears to be a valve rocker arm cover just to the right of the rag. Perhaps they were performing a periodic lubrication of the rocker arms. In the photograph below, Ms. Crabb's grandmother looks at the camera while walking toward the rear of the airplane, parasol over her right shoulder.

"Pride of Detroit," Calcutta, India, September 6, 1927 (Source: Crabb)

|

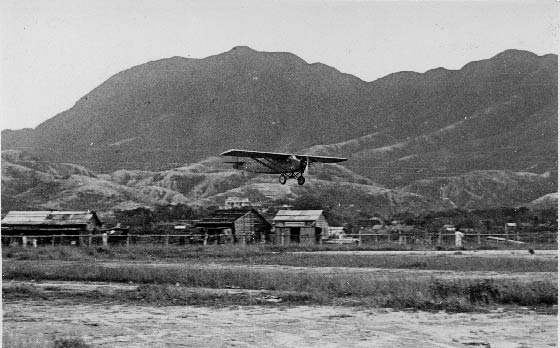

Below (added to page February 2, 2010) are two crisp photographs courtesy of a site visitor from England, Vic Flintham. Notice on this first image "WAYCO" painted on the bottom of the starboard wing. The slightly balding gentleman studying a document under the port wing looks like Edward Schlee. The location has been identified by site visitors as Kai Tak Airport, Hong Kong.

"Pride of Detroit" on the Ground, Kai Tak Airport, Hong Kong, Ca. 1927 (Source: Flintham)

|

We see the "Pride of Detroit" in the air in the next image. From the flight attitude, it appears to be approaching to land. The sign on the building in the background, which probably would positively identify the location, is tantalizingly out of focus.

"Pride of Detroit" on the Ground, Kai Tak Airport, Hong Kong, Ca. 1927 (Source: Flintham)

|

Interestingly, the CAA file for NC857 noted that there were "....no papers on

file on the use of the aircraft for a 1927 Atlantic flight

and on to Tokyo, Japan, crewed by Edward Schlee and William

Brock".

Image, above, from the New York Times, shows the airplane in cross-section, with

fuel tanks and navigation equipment installed, as it made

its round the globe flight. There was mention that the aircraft

was named "Pride

of Detroit". On inspection a year later on August 15,

1928, it had the auxiliary gas tanks removed and seats reinstalled.

A letter in the CAA file indicated that it was Schlee and

Brock's intention to place the aircraft in the Ford Museum

in Dearborn. The registration was officially cancelled

December 19, 1929. The aircraft is, in fact, in The Ford

Museum.

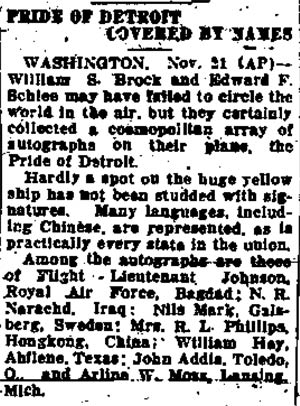

Oswego (NY) Palladium-Times, November 21, 1927

|

At Aden, the airplane, and pilots Brock and Schlee, were

a little less than midway in their round-the-world flight.

Brock and Schlee are not identifiable in the image, unless

the person in the white trousers, far left, is one of them.

This source

states of the pilots, "Reporters remarked that the two

fliers emerged from each stop fresh and smiling, wearing white

summer suits with blue bowties. They could have been a couple

of casual tourists." Under magnification, all the people in the photo appear to be uniformed soldiers.

Brock and Schlee departed on their journey on August 27,

1927. They originally intended their flight to be a world

flight, but they abandoned their attempt, after reaching Tokyo,

Japan, because of poor weather over the Pacific Ocean. After

flying across the Atlantic, they reached Japan, from England,

in eighteen days, flying 145 hours and 30 minutes and covering

12,995 miles. They returned to the United States by ship,

to great accolades in Detroit.

Back in the U.S., as evidenced by the article, left, they had made the "Pride of Detroit" a collector's item with all the autographs acquired during their voyage. Again under magnification, the airplane the airplane does not appear to have any visible writing on it at this point in its journey. Note that the airplane is yellow.

---o0o---

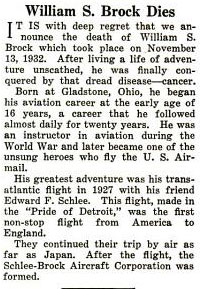

Brock Obituary, Popular Aviation, January, 1933 (Source: PA)

|

Brock died November 13, 1932. One obituary appeared in the January, 1933 issue of Popular Aviation (PA), right.

Site visitor R.R., of Urbana, OH, sent along the following

four newspaper articles published in the Urbana Daily

Citizen in 1945. Thanks to him.

This is a fine link

for William S. Brock. R.R. shared his news articles with

that site also. You'll see them there. This

one is a good link, too. Both links show pictures

of Brock; the latter Schlee.

Parts of the articles below are derived or quoted from other

newspapers, and some of the language is semi-sensational prose.

A fun journalistic vignette.

ARTICLE I

Source: Urbana Daily Citizen Urbana, OH,

July 17, 1945

Headline: Billy Brock, An Unsung Hero Of Early Aviation:

Long Cross-Country Flight Ends Near Urbana

"We recently ran across an article published in a little

Pennsylvania Plant newspaper. It was dated July 12, 1927,

shortly after Lindbergh’s flight across the Atlantic.

We think it is worth republishing now, to draw a contrast

between the pioneer flying during World War No. 1 and the

exact precision of modern flying. But the precision of today

would be impossible without the daring and faith of yesteryear.

The article is also of direct local interest, because the

destination of the flight was Springfield and Urbana, and

because the Billy Brock of the article was born in West Liberty

and his mother lived in Springfield. Here is the article:

“We paid our written tribute last month to Charles

Lindbergh and it is with no thought to belittle his achievement

that we write what is to follow. We know that Lindbergh would

echo a hearty ‘Amen’ to our present toast. That

is: “To the unsung heroes of the air.”

“We are looking back a little over eight years ago,

and there comes to mind another airplane flight. It was made

at the very end of October, 1918, while the war was still

raging. Billy Brock, who was about twenty-two years old, was

an instructor at Park Field in Tennessee, an Army Flying Field.

He had been training other boys to fly, so that they could

go overseas to help win the war. He was so good that they

wouldn’t let him get away from this side of the pond.

“Toward the end of October in the year 1918, there

was no thought or talk in the army, on this side at least,

of any armistice or early end of the war. They planned on

many more months. In fact, at Park Field they were all set

with overseas equipment, as they were at all the other flying

fields. The plan was to leave only a skeleton organization

behind at each field, to pull up stakes enmasse, and establish

an overwhelming American airplane force-in France, to overwhelm

Germany from the air.

“Knowing all of this, Billy Brock wanted to fly from

Park Field to his home in Springfield, Ohio, to say good-bye

to his mother. That was 600 miles away, and in America only

two or three had ever flown a longer distance, and no one

had ever flown nearly that distance in a Curtiss Jennie. But

Billy had been flying since he was 15 years old, and he was

good. So, the commanding officer gave him permission to make

the flight. He was to take another Army officer along as a

passenger. The ship chosen was one of the first type of Curtiss

training planes, a J.N.4-A, with a Curtiss O.&.5 [sic]

motor. It was the only J.N.4-A at the field. They were then

using J.N4-D’s, an improvised type of plane. All the

other J.N.4-A’s had been junked, and this one had been

put out of service. Being out of service some of the boys,

in their spare time, had taken the controls out of the front

cockpit and had built in a 20 gallon gasoline tank instead

of the usual 10 gallon tank. That was the reason that Billy

selected this discarded ship -because it could carry more

gasoline. But it had this disadvantage-the installation of

the larger tank had necessitated the removal of all the instruments,

they being on the front dash, so the ship had no compass,

no altimeter, no wind-drift indicator, not even a gasoline

or an oil gauge. Its maximum speed was about 75 miles an hour,

and its ceiling was about two thousand feet.

“At daybreak on a Friday morning, the ship was ‘on

the line.’ No other ships were out, because the fog

was so bad you could not see 50 yards ahead. Flying had been

called off for the forepart of the morning, and the only people

on hand besides Billy and his passenger were their wives,

a couple of hanger-men, and Red Thompson, a buddy of Billy.

The passenger climbed into the front seat and fastened his

safety belt. Billy walked around the ship a couple of times,

then climbed in and strapped. Red Thompson told Billy what

a fool he was to take off in such a fog. Billy replied in

proper Army repartee, and then Red handed Billy a horseshoe

and a rabbit’s foot. These two buddies, who both came

from Springfield, and who had flown together for years before

the war, had several times handed back and forth these same

charms."

ARTICLE II

Source: Urbana Daily Citizen Urbana, OH,

July 18, 1945

Headline: Billy Brock, An Unsung Hero Of Early Aviation:

Long Cross-Country Flight Ends Near Urbana

"At conclusion of Tuesday’s installment- the first

of a four part story- Billy Brock, accompanied by a pal from

Springfield, Ohio, were about to take off in an outmoded army

plane for a cross-country flight from Tennessee to Urbana

and Springfield.

" Enshrouded by heavy fog, with no navigation instruments

to guide them, the two flyers gambled their destiny on a horseshoe

and a rabbit’s foot which they had decided to take along

as good luck tokens.

The story continues: “The ship took off. The fog was

so thick, it was sticky. Nothing could be seen, and they had

no altimeter, but they could tell by the feel that the ship

was climbing all right. In less than 20 minutes the ship came

out of the fog into clear air, which would have been a relief,

except for the fact that there was no sight of ground in any

direction, nothing but dense banks of clouds underneath. They

had no compass and no chart-only a six-inch pocket map of

Tennessee and Kentucky. Billy had planned on following the

Louisville and Nashville railroad, but they couldn’t

see it. The sight of the sun helped little, as there was a

side to rear gale blowing, which might have been 30 miles

an hour or it might have been 60. But they had no means of

telling its strength or its directions, as they had no wind-drift

indicator. It was afterward learned that it was over 50 miles

an hour.

“They flew above the clouds, without a sight of the

earth, for a couple of hours, without knowing whether their

altitude was two thousand or five hundred feet. Finally, Billy

called to his companion: “We ought to be about over

Paris (Tennessee); I’m going to cut down and find out.”

He started a tight spiral, but in less than a minute he almost

jerked the plane apart, coming out it took away some branches

out of the top of a tree, missed a couple of buildings by

less distance than was comfortable, and found that he was

squarely over the heart of Paris, Tennessee. It hadn’t

been clouds he had been flying over, it was clouds and fog

right down to the ground.

“Billy Brock had flown for two hours with no sight

of the ground, no compass, no instruments of any kind, and

with a terrible side-tail wind of unknown strength or direction.

And he not only guessed, he knew, within less than a mile,

exactly where he was. How did he know it? You have learned

how cats know their whereabouts. Perhaps it was something

like that, only more marvelous, as this was all done in the

air.

“Well, Billy got his ship flattened out, and was again

on his way. It wasn’t long until they left the clouds

and fog, and were over Kentucky. Worry about gasoline supply

advised a landing, and they landed in a stubble field at the

edge of the town of Russellville. We will omit some of the

details of the take-off from Russellville. In that take-off

they came nearer death than at any time on the flight. It

was a matter of inches several times-a short, soggy field,

loggy gasoline, a nose-heavy ship, telephone wires straight

ahead, a zoom over the wires that anyone would have said was

impossible, a vault over some more wires and a railroad track,

a gliding squash into a soft field across the track, but with

enough headway to keep going and to finally climb fifteen

feet in the air, but with a house straight ahead. There wasn’t

time or altitude to turn, so Billy went straight for the house,

and just as he came to it, he threw the ship into a vertical

bank, one wing missed the chimney by not more than a couple

of feet, and the other wing came that close to the ground,

but they cleared the house.

“They finally gained altitude, and it was straight

and clear flying over the edge of the mountain district of

Kentucky. That is the country that, form the air, has nothing

underneath for well over a hundred miles but mountains, forests,

snake-like rivers, small clearings and intermittent small

lakes and ponds. A forced landing would have meant the tree

tops.

“They landed near Louisville for the night, took off

the next morning in a blinding rainstorm, tried to get above

the rain, but the higher they went, the more it was sleet

instead of rain. They kept on toward Cincinnati, got out of

the storm, then turned north, did some stunts over Springfield,

and then landed on the golf course of the Springfield Country

Club. They had lunch with Billy’s mother, then took

to the air again, and landed on a farm just west of Urbana,

where the passenger had relatives.

“Billy Brock, twenty-two years old, had resurrected

a J.N.4-A out of the junk pile, and had flown it, with no

instruments and with nothing but genius to guide him, in bad

weather, over a wilderness country, and part of it was blind

flying; then, he turned around and made the return trip, which

was even worse, because the wind was against him.

“Billy Brock didn’t get overseas, because they

kept him on this side. Few people have ever heard of him.

The last we heard of him, about four years ago, he was taking

up passengers for five dollars an hour, when he could get

the passengers. He is unknown to fame, but he was one of the

pathfinders in aviation. He is an unsung hero.”

ARTICLE III

Source: Urbana Daily Citizen Urbana, OH,

July 19, 1945

Headline: Billy Brock, An Unsung Hero Of Early Aviation:

Around-the-World Flight Ends in Japan

"In Wednesday’s installment we reprinted an article

written in July, 1927 about Billy Brock’s airplane trip

from Tennessee to Springfield and Urbana during the World

War No.1. When that article was originally written, no news

had been given out as to Billy’s plan to fly around

the world. He made that world flight in the late summer of

1927, and that same Pennsylvania plant newspaper had an article

about it in its issue of Oct. 12, 1927. Here is the article:

“In our issue of July the twelfth we printed an article

which was entitled: ‘Unsung Heroes of the Air’.

We were inspired to write that by Lindbergh’s ocean

triumph. When we printed that article we had no idea that

Billy Brock had intended to try what he has just done. You

will remember, we wound up our article of July the twelfth

by the statement that the last we heard of Billy Brock, he

was taking up passengers at a modest fee.

“Well, you must have read about the around-the-world

flyers, who started out to fly around the world, and who got

as far as Japan-Brock and Schlee. The Brock who flew this

airplane is the same Brock of whom we wrote. He is about thirty-two

years old, and is a courageous, but an exact and careful flyer.

“Here is what the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette said about

their flight in the editorial column of August 20th, the morning

after they had landed in England:

“The successful negotiation by William S. Brock and

Edward Schlee of the first leg of their projected around-the-world

trip by air, completing the first non-stop trans-Atlantic

flight from America to England naturally raises hopes for

the achievement of their entire object. They are seeking to

beat the globe-circling record of twenty-eight days, fourteen

hours and thirty minutes, made by Edward Evans and Linton

Wells last year by utilizing steamer, railroad, automobile

and airplane; Brock and Schlee, depending wholly upon their

monoplane, Pride of Detroit, expect to make the trip in twenty-eight

days or less. Their covering the 2,350 miles from Harbor Grace,

Newfoundland, to the airport at Croyden, England in twenty-three

hours and twenty minutes is a good start on their schedule.

The extraordinary thoroughness with which this trip was planned

gives a practical interest to it along with that which may

be merely of the thrill type. Schlee, the backer and Brock,

the pilot, had been at work on the preparations for a year.

With the mapping out of their course, there was also provision

over the route of fuel and service stations. The Pride of

Detroit was built with the same care, and tested. It won by

a large margin the Ford trophy against a field of fourteen

specially prepared planes in a 4,200 mile test. The total

mileage of the course in this undertaking is 22,067, with

a total of 240 hours allowed for flying. However the object

of the trip may be viewed, the thoroughness of the preparation

for it meets the growing demand against recklessness in setting

out on air journeys involving long flights over water’

“Brock and Schlee flew no further than Japan, and abandoned

their trip there, partly because there was no gasoline supply

at the Midway Islands, their next objective, and partly because

of the hundreds of cablegrams they received begging them not

to try to fly across the Pacific Ocean, including a ‘request’

from President Coolidge. They realized that after the large

number of deaths in attempting ocean flights, an accident

to them would retard the progress of aviation. And they were

more interested in the development of aviation than they were

in any personal triumph. But at least they demonstrated that

hard work, studious preparation, and careful courage and determination

are essentials to successful flying.”

"This is the same Billy Brock who was born in West Liberty,

raised in Springfield, and who began flying before he was

sixteen years old. In a later account, we will tell you something

about how Billy learned to fly."

ARTICLE IV

Source: Urbana Daily Citizen Urbana, OH,

July 20, 1945

Headline: Billy Brock, An Unsung Hero

Of Early Aviation: West Liberty Boy Began Flying When Eleven

"(EDITOR’S FOREWORD: These stories concerning

the career of Billy Brock, the West Liberty boy who helped

pave the way for modern aviation, were prepared by one of

his close personal friends and Army air corps associates Attorney

Edgar W. Tait, 403 Scioto Street. It was Tait who, as post

adjutant at Park Field, Tennessee during World War I, awarded

Brock the lieutenant’s commission which transformed

him from a civilian army flying instructor to a full fledged

military pilot. The commission was awarded at Wright Field.

"Since then the two men maintained a close personal

friendship visiting one another whenever possible. Their last

meeting was in Pittsburgh shortly before Brock’s death.

"In the past three articles, we have written about Billy

Brock of West Liberty and Springfield. We would like to tell

you something of this boy’s craving urge to fly, and

of his flying education. Some of these facts were proddingly

picked out from Billy, for he was not much of a talker about

himself. Some of this story was furnished by others who knew

him. Here is the story:

"The story starts at West Liberty, when Billy was eleven

years old. The Wright Brothers had made their Kitty Hawk flight

a few years before. They had conducted their experiments at

an historic place between Springfield and Dayton. That part

of Ohio was already air-conscious, and Billy began to think

of nothing but flying. He started to work, building a pair

of wings. He used whatever sticks he could pick up around

the neighborhood. He managed to beg a couple of old sheets

from his mother, for the wing fabric. Finally, the wings suited

him. He strapped them onto his arms, climbed to the top of

his father’s barn, and jumped off. The experiment was

not entirely a success. He glided a few rods, the wings smashed

on the landing, but he broke no bones.

"Four years later, when he was fifteen years old, Billy

heard about Glenn Curtiss’ flying school at Hammondsport,

New York. He had a little money saved, just enough to pay

his railroad fare there, so off he started for Hammondsport.

He walked into Glenn Curtiss’ office, and said he had

come to learn to fly. Glenn Curtiss asked him how old he was

and he replied, “Eighteen.” He was well developed

for his age, so he got away with that. Then Curtiss said:

“The tuition will be $150.” Billy said: “Why

I never thought about you charging for teaching, and I don’t

have that much money.” Curtiss said: “How much

do you have?” and Billy answered, “Sixty-five

cents.” Curtiss said: “Well, you had better write

to your folks for enough money to get home. In the meantime,

we can’t let you starve. I’ll let you help the

cook in the kitchen, to pay for your board until you hear

from your folks.”

"So, Billy went to work in the kitchen. But it was okay

for Billy to make friends, and he was soon chummy with the

flying instructors. He coaxed one of the instructors to take

him up, and before they had landed, Billy was getting some

flying instruction. He went up every day, and in less than

a week he was soloing-all unknown to Glenn Curtiss. Not satisfied

with this, Billy put in another week of learning every stunt

the instructor knew. Finally, the instructor said, “Kid,

you are as good as I am.”

"Then, Billy walked into Glenn Curtiss’ office

again-the only time he had been there since his first arrival

visit. He had made a point of keeping out of Curtiss’

way. Curtiss looked up from his desk, and said: “What,

are you still here? Well, what do you want?” and Billy

replied: “I want a job as an instructor.” A queer,

startled look appeared on Curtiss’ face, and Billy said:

“No, I’m not crazy. One of the instructors has

taught me. Come out and watch me.” Curtiss asked the

instructor, and he said: “Yes, I guess I shouldn’t

have done it behind your back. But the boy is a born flyer.

He is good.” So, Billy took the ship up, put it through

its paces, spun it, looped it, did every stunt that was then

known, and finally made a perfect landing. Curtiss said: “Take

me up and do it all over again.” When they landed, Billy

Said: “Mr. Curtiss, do I get the job?” and Glenn

Curtiss replied: “You do.”

"So, in the year 1912, at the age of 15 years old (although

he stuck to his 18 years of age story), Billy became a flying

instructor. He continued as an instructor and stunt flyer

until we go into the war in 1917, when he became an army flying

instructor. There, his finished students were as many as those

turned out by any other instructor, and when he said they

were ready for their wings, they were ready and they were

good.

"We have told, in previous articles, about Billy’s

career after the war, how he barnstormed, took up passengers,

instructed, and finally flew across the Atlantic, across Europe

and Asia, to Japan. In the issue of March 29, 1928 of the

Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, Havey Boyle, sports writer and columnist

wrote the following:

“He is between 35 and 40, of medium height, and inclined

to heaviness. His hair shows a streak or so of gray. A short

mustache is becoming. His eyes are clear blue. He achieves

neatness in dress without showing any signs of study in this

regard. He has a naturalness-a mixture of justifiable pride

and becoming modesty. His name is Billy Brock-and all he did

was to fly across the ocean with a partner-Eddie Schlee. You

remember how we read of their hop-off, of the anxious while

they rode through the night through the fog and ice, and how

at last they landed safely on the other side.

“Billy Brock was in Pittsburgh to attend the airplane

show. He is now a salesman, selling the kind of ship he and

Schlee used in making their historic flight. I have been close

(I mean close in the sense of feet and inches) to such gentlemen

as Dempsey, Ruth, and Tunney and a few others, but I never

got quite the emotional thrill from such propinquity as I

got out of studying and talking a few moments with this youngish

Billy Brock, who defied death successfully in a flight across

the ocean.

“By now his story is an old one. He took off when three

other planes were making ready. Two of those planes and their

occupants were lost. The third didn’t get very far before

it was forced to land, a failure. There were moments, Mr.

Brock said the other evening, when he couldn’t help

but feel that the venture was going to lose-those periods

when there was nothing but ice and fog to cut through. But

it was not his story, so much as the fact that here was a

man in good health who had stepped into a plane to take a

ride with death. I thought, too, as he talked, of how many,

many centuries from now his name and picture will be in the

history books and encyclopedia. There is a kick to being so

close to a man of-consider this-timeless and endless fame.

"So wrote Havey Boyle, sixteen years ago.

"Billy was never injured in flying, nor was any of his

passengers. He never had a crack-up that cost more than a

ripped wing or a splintered landing gear. Army officers, up

until the time of his death, said Billy was the most careful,

the safest, the most scientific, and yet, when necessity required,

the most daring flyers our nation had yet produced.

"Billy died of cancer a little more than twelve years

ago [in 1932]. He was flying until a month before his death."

A final photograph of Brock and Schlee's global flight Stinson , courtesy of Guest Editor Bob Woodling, is below. The registration number is distinct. The exact date and location are unknown.

Stinson SM-1 NC857, Date & Location Unknown (Source: Woodling)

|

---o0o---

Dossier 2.1.56

THIS PAGE UPLOADED: 06/13/05 REVISED: 07/07/05, 01/16/06, 01/18/06,

03/27/06, 12/31/07, 08/29/08, 02/02/10, 03/21/14, 06/25/14, 09/12/14, 09/13/15, 07/13/17, 10/05/19

|