|

Francesco de Pinedo, 1920s (Source: Woodling)

|

While celebrity certainly wasn't rare among the pilots and passengers (and airplanes) of our Registers, Francesco de Pinedo ranked among the top dozen or so.

de Pinedo signed the Floyd Bennett Field Register on what appears to be May 23, 1933. The landings before and after his signature were dated before the 23rd, so de Pinedo was chronologically out of sequence in the Register. What he didn't know was that he had about three more months to live, and that he would die within yards of his signature in the Register.

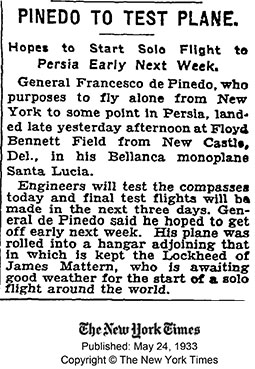

The New York Times, May 24, 1933 (Source: NYT)

|

At his visit, de Pinedo piloted solo the Bellanca he identified as NC13199, a model J-3-500 (S/N 3007) that he had named "Santa Lucia." He arrived at Brooklyn from "Newcastle." We know he meant Newcastle, DE, because this article from The New York Times (NYT), left, marked his arrival. As well, his Bellanca airplane was manufactured in Newcastle. His destination was Floyd Bennett Field. This article corroborates the date he entered in the Register. Note mention of James Mattern, who signed the same Register page as de Pinedo.

The New York Times, May 10, 1933 (Source: NYT)

|

The New York Times, May 9, 1933 (Source: NYT)

|

He was in the U.S. (landing here by ship December, 1932) to attempt a non-stop flight from New York to Iraq. Preparations went on for months, but, because of weather and other details, he didn't depart until September, 1933. His intentions for this flight were reported in The New York Times, May 9, 1933, left. This was not the first long-distance, global flight he planned and executed, below.

de Pinedo was born in Naples, Italy February 16, 1890. Google "NC13199" and there is only one hit. But Google "Francesco de Pinedo" and there are over 50,000 hits for his name as of the upload date of this page. Besides wiki, some sites for you to visit describe de Pinedo's early life, his record flights during the 1920s (Australia, Japan, America, 1925-1927; Canada, 1927), and his involvement with the Italian government during those years (aeronautical policy; Regia Aeronautica Italiana). During his world tour, de Pinedo was fêted by heads of state and other dignitaries. He met with U.S. President Coolidge He received the Distinguished Flying Cross in March, 1927. A photograph at the Library of Congress commemorated his vist with Coolidge.

His glory during the 1920s turned to doldrums as the 1930s developed. Because of political issues, some of which are discussed in the links above, he was relegated to remote, lower-level government desk jobs, like air attache in Buenos Aires. He decided not to tolerate these menial positions, because he felt he had much more flying to do. He quit, and in 1932 sailed to the U.S.

The New York Times, May 14,1933 (Source: NYT)

|

As intoduced above, Floyd Bennett Field was the venue for de Pinedo's last record attempt. There was excellent news coverage of his plans and preparations during the last months of his life. We can imagine they were spent modifying his airplane for the flight, route planning and managing the political issues and permissions encumbent upon an American airplane with an Italian pilot flying through the air spaces of numerous countries. These activities were all reported in newspapers of the day. The New York Times, May 10, 1933, reported work on his engine at Hartford, CT, above right. Preparations of the airplane at Newcastle included a siren to keep him awake, and an altimeter with an altitude-sensitive switch that would turn on a stream of water aimed at de Pinedo's face if he drifted too low. Delays, descirbed in The New York Times, May 14,1933, prevented his departure, right.

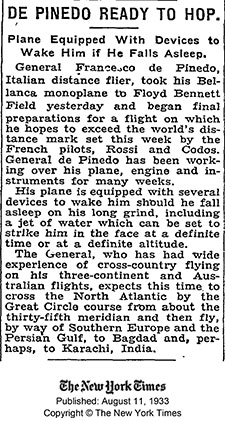

The New York Times, August 11, 1933 (Source: NYT)

|

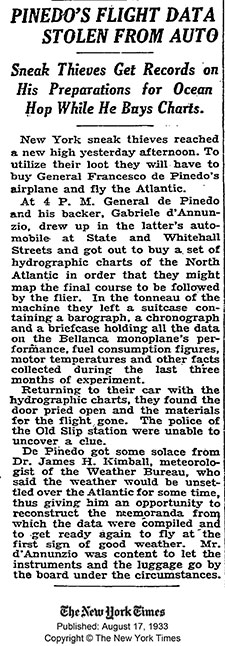

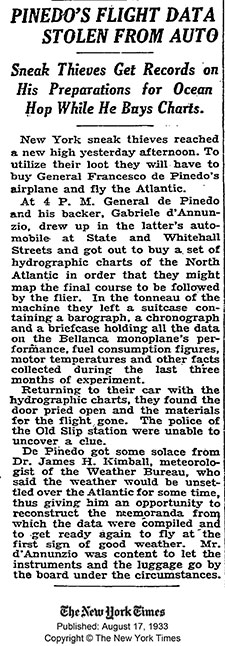

The New York Times, August 17, 1933 (Source: NYT)

|

Note that Dr. James H. Kimball of the U.S. Weather Bureau was the same meteorologist who advised Charles Lindbergh on weather before his 1927 flight to France.

The Times of August 11, 1933, a date that reflects the three-month delay in his plans, announced that de Pinedo was ready to fly, left.

Then his flight planning data was stolen, as reported in The New York Times, August 17, 1933, right. The loss represented months of work, but it did not deter him.

On September 3, 1933, he attempted to fly nonstop from Floyd Bennett Field to Baghdad, Iraq. If successful, this flight would be the longest continuous flight ever made. de Pinedo was flying NC13199, which had been modified to contain 1,030 gallons of gasoline (newspapers reported various numbers around 1,030). The airplane was severely overloaded. After a short taxi sequence, the airplane went out of de Pinedo's control and crashed. Within seconds it burst into flame and took his life. At the link is a video, with sound, that documents the takeoff roll and the resulting crash. The Time magazine information from 1933, below, appeared as documentation on the same page as the video.

From Time magazine, 1933

"Observers who watched a middle-aged Italian in blue bedroom slippers, grey sweater, blue serge suit and grey derby hat get into a big Bellanca monoplane at Floyd Bennett Field, Brooklyn, early last Saturday morning, felt that they were witnessing something unusual to the point of eccentricity. General Francesco de Pinedo was taking off alone for Bagdad, 6,300 mi. away. The cockpit of his ship, the Santa Lucia, was a museum of gadgets and curious supplies—eight watches, two colored kites, fishing tackle, a stomach pump to draw liquids from six vacuum bottles, a fresh air mask, a siren and water-squirter to wake up the pilot if he dozed. He was going to sit over the oil tank, so that the uncomfortable heat would keep him awake. As he yelled good-by a fanatical gleam was in his eye.

"Major J. Nelson Kelly, manager of the field, who with his wife and pilot George Haldeman followed the plane in an automobile [NOTE: you can see, at the far right of the screen, their car chasing the airplane early in the takeoff sequence] after its start up the runway, said later that he felt sure de Pinedo would stop after his overladen ship, reeling drunkenly under 1,030 gal. of gasoline, veered almost off the concrete as it got up to 80 m.p.h. But the man in the cabin was obsessed. He straightened the Santa Lucia and roared ahead. He lifted the tail. . . .

When a heavy plane's tail is lifted, torque from the propeller or giving it the gun too quickly may slew the ship sideways for an instant, heavily taxing the pilot's skill to keep his course. That apparently happened to de Pinedo, and his skill failed. Not yet going fast enough to rise, his ship slewed sharply, heading straight for the field's administration building where 150 persons stood watching. Then it slewed further as though, foreseeing danger to many, de Pinedo chose disaster for himself alone. The thundering Bellanca crashed through a heavy wire fence, shearing off the landing gear. Its engine still roaring, it plunged on some 25 yd. before flumping on its side. Bright little flames were trickling up to the gas tanks. Watchers could see de Pinedo, who had been pitched through the windshield, writhing on the ground just under the ship's nose. Next second plane & pilot were a towering holocaust.

"'He simply forgot what he knew,' said his mechanic.

"'His pride killed him,' said his closest friend, Ugo d'Annunzio (son of Poet Gabriele).

'''De Pinedo today is not the same man he was several years ago. He had deteriorated physically and psychologically as the result of an automobile accident in Buenos Aires in May, 1931,' said Giornale d'Italia in Rome.

"All three verdicts added close to the whole truth. It was eight years since the Marchese de Pinedo, rich, young and brashly daring, was the toast of Italy for his 35,000-mi. flight to Australia, Japan, India and return; six years since his circling of Africa, South America and the U. S. Mussolini made him a General and Chief of Staff for Air under Italo Balbo.

"His first major mishap had come at Roosevelt Dam; a bystander's careless match that burned up his ship. Then he came down at sea, had to be towed for seven days into Fayal. Now came worse. Some say it was the House of Savoy, angered because he dared court Princess Giovanna (today Queen of Bulgaria). Some say it was Italo Balbo, jealous of de Pinedo's acclaim. Some say it was because de Pinedo "forgot" about a half-million-lire fund raised for him by Italo-Americans to buy a new plane. Italo's hero was suddenly, drastically demoted, attached obscurely to the embassy in Buenos Aires. There he played polo and hunted. He kept his peace with good grace until this year—the year of Balbo's triumphal armada flight—he appeared in New York intent to the point of desperation on flying farther than any man had flown, all alone.

"The U.S. Government and the City of New York sponsored an imposing memorial service for Pinedo, with his remains being carried in a solemn procession to St. Patrick's Cathedral, while a squadron of American military planes circled overhead. The coffin was then placed aboard the Italian liner Vulcania and taken back to his homeland for burial with full military honors." |

Besides the car chasing NC13199 early in the film, you can also see, at the end of the movie while the airplane burns, some of the 150 people who watched the attempt from in front of the administration building. The aftermath of the flight attempt and crash was published in The New York Times, September 3, 1933, below.

Aftermath of de Pineodo's Record Attempt and Crash, The New York Times, September 3,1933 (source: NYT)

|

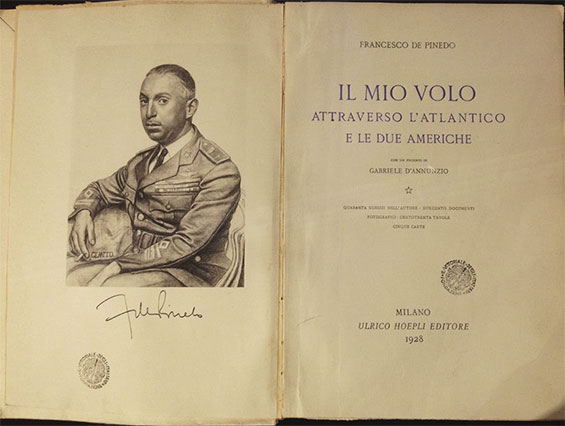

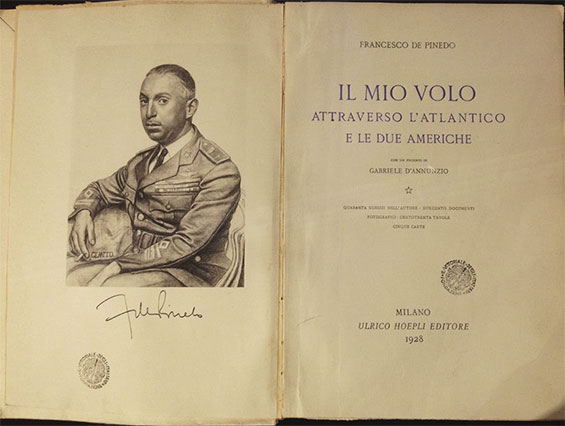

de Pinedo was 43 years old, a bachelor, and rumored to have a fortune of $4,000,000. He authored a book in 1928 describing his flights across the Atlantic and his tours of North and South America. The fronticepiece and title page are below. Compare his signature with that in the Register.

de Pinedo Book, 1928 (Source: Woodling)

|

---o0o---

THIS PAGE UPLOADED: 12/29/16 REVISED:

|