|

Casey Jones was born January 11, 1894 at Castleton, VT. He was one of the older pilots to sign the Davis-Monthan Register. He has an incomplete timeline at the link summarizing his activities during his life. He touched many aspects of Golden Age aviation, from managment, to racing, flight training and writing for the popular press. Below he appears smiling sitting in a cockpit of an unidentified aircraft; date and location unknown. Photo from an old trunk, courtesy of site visitor GCK from Tennessee.

Casey Jones, Date & Location Unknown (Source: GCK)

|

On the racing front, below, courtesy of site contributor Andy Heins, is a photograph of Jones (R, with helmet and goggles folded in-hand) with Jack Frost (not a Register pilot). This photograph was taken before August, 1927, because Frost disappeared that month somewhere over the Pacific Ocean during the controversial trans-Pacific Dole Race. They stand in front of Jones' Curtiss racer, which can be seen in another photograph below.

Casey Jones (R) and Jack Frost, Pre-August, 1927, Location Unknown (Source: Heins)

.jpg) |

He landed once at Tucson. He arrived solo on Thursday, October 6, 1927 flying an unidentified Douglas aircraft. Based in Chicago, IL, he arrived at Tucson from Los Angeles, CA about 6:00PM. He remained overnight in Tucson, departing the next morning at 6:45AM eastbound to El Paso, TX. "NAT" was written in aircraft registration number field of the Register.

Below, shared with us by site visitor Russ Eggert, is a U.S. Postal cachet from February 2, 1930. It commemorates the 1930 New York Aviation Show.

Casey Jones, Signed U.S. Postal Cachet, New York Aviation Show, February 1, 1930 (Source: Eggert)

|

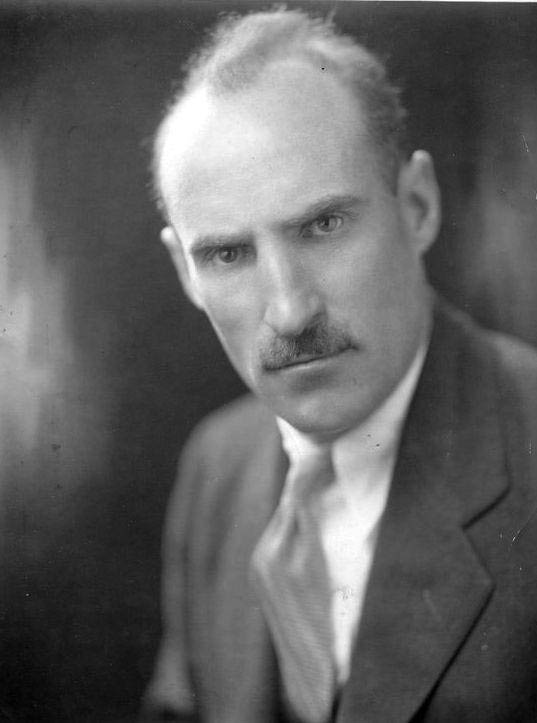

Below, a photograph of Jones, ca. 1931-32, shared with us by friend of dmairfield.org, John Underwood.

Charles Sherman "Casey" Jones, Ca. 1931-32 (Source: Underwood)

|

The caption on the back of the photograph states that Jones was vice president of public relations for the Curtiss-Wright Corporation about this time, and that they were distributors for Monocouple aircraft. A Monocoupe stands behind him. Jones would be about 37 years old in the photograph, residing on Long Island, NY with his wife and two children. Other photos of Jones are at the link in the Klein Archive on this site.

A sytlized biography is in Time Magazine, November 7, 1932. He had just resigned from Curtiss-Wright two weeks previous to publication. About this time he founded a training facility that exists to this day as the Vaughn College of Aeronautics and Technology. Note with interest at the link that the large mural painted by Register pilot Aline Brooks is stored at the College.

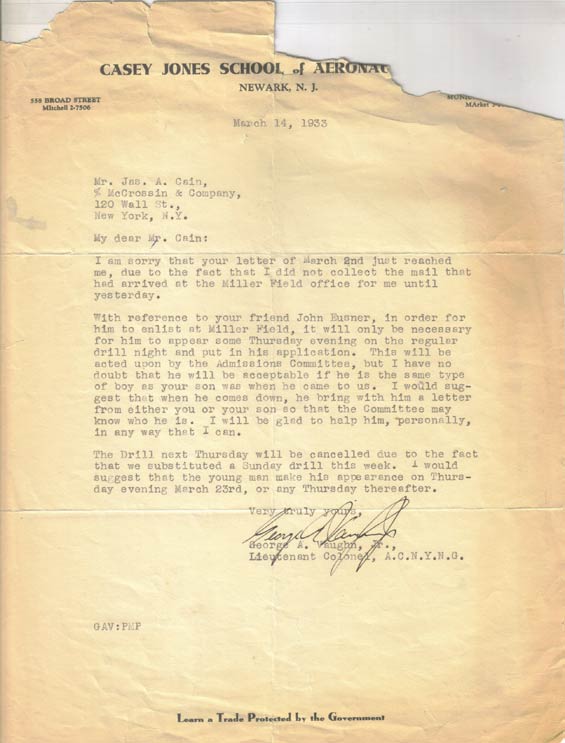

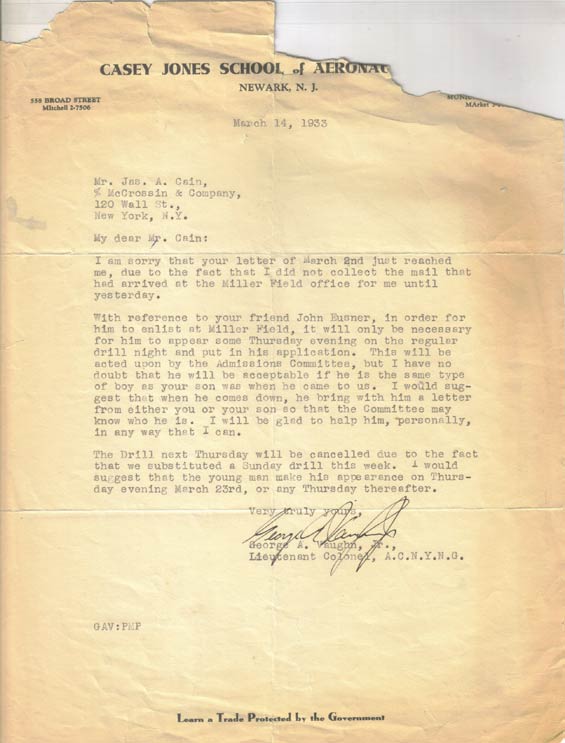

Below, a letter from March 14, 1933 shared with us by site visitor Jeff Staines. He says about the letter, "It is a letter typed on Casey Jones School of Aeronautics letterhead dated March 14, 1933 and signed by Lieutenant Colonel George A. Vaughn Jr., the second-most scoring WW I Ace that survived the conflict. He also was a stunt pilot and racer who was affiliated with Casey Jones and his school. At that time he was also Commander of the newly-organized New York Air National Guard. The letter details the method used to gain access into the Air National Guard at Miller Field, NY for certain people known to Vaughn."

Letter, March 14, 1933 (Source: Staines)

|

Below, courtesy of Andy Heins, are three undated photographs of Jones. The first one appears to be an official military photograph (the inscription at the bottom is typical of military photos, but is unreadable). Jones signed this photo to Al Lodwick, who was flight operations manager for Howard Hughes' round-the-world flight in 1938. Note the absence of wheel covers when compared to the other photo of this airplane at the top of this page.

Casey Jones With Curtiss Racer, Date & Location Unknown (Source: Heins)

|

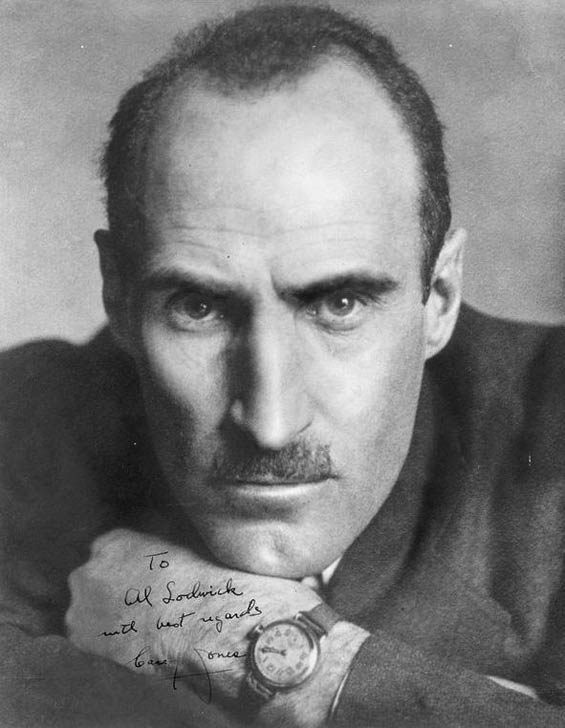

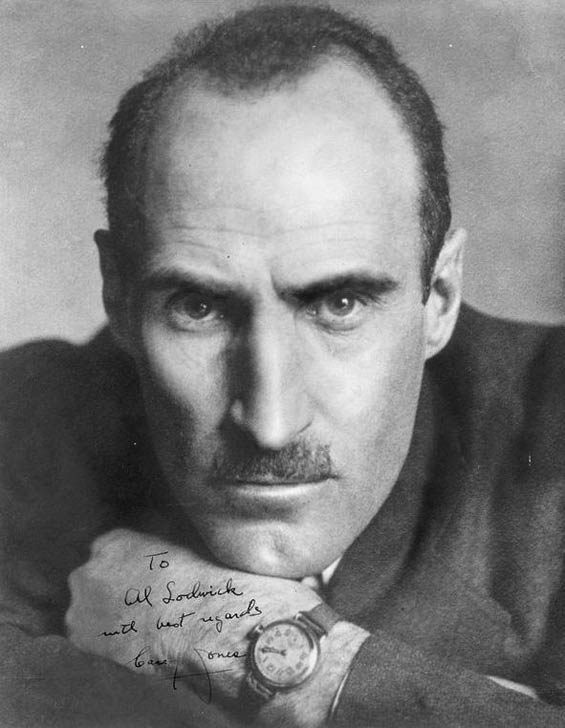

Below, another photograph, a formal portrait, signed "with best regards" to Lodwick. Although the date is unknown, the time was 2:10, probably PM.

Casey Jones, Date & Location Unknown (Source: Heins)

|

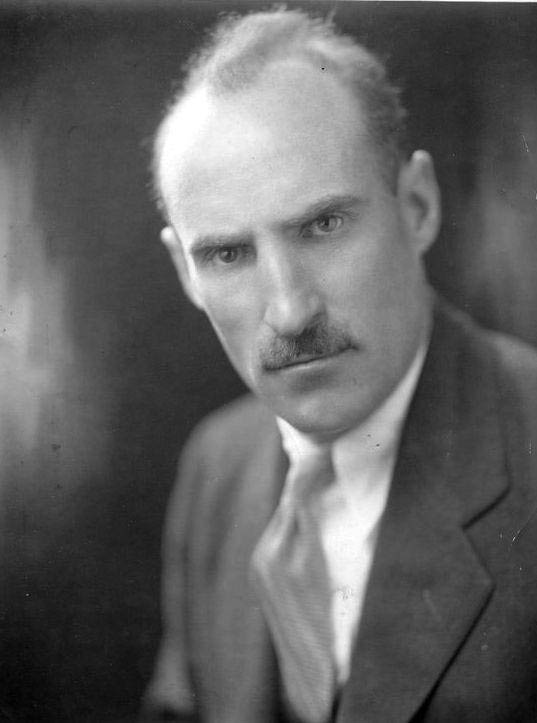

Below, an unsigned formal portrait of Casey Jones.

Casey Jones, Date & Location Unknown (Source: Heins)

|

Jones was a participant in the Ford Reliability Tours of 1925 (the first one) and 1926. The Forden REFERENCE, chapter 10, says this about him (published in 1972).

Charles S. Jones was called "Casey," an appropriate name for an aviator, who like the legendary locomotive engineer kept a strong hand on the throttle. The aviator Jones was a Vermonter who planned to be a lawyer, worked instead as a physical education instructor, and became a flyer in the World War. Then he joined the Curtiss organization, was an instructor, test pilot, salesman, inveterate racer, company executive. He competed in the first two air tours. Jones started his own School of Aeronautics in 1932 and it is still going at La Guardia Airport, New York, as the "Academy of Aeronautics." Some time after Casey Jones had retired in St.

Thomas, The Virgin Islands, we asked him to recall the most exciting and interesting times in fifty years of flying. "Well," he said, "I enjoyed every minute of it. Every day, every year. Never did seem like work." |

Compare Jones' recollection of his life in flying with that of fellow Register pilot Earl Rowland's.

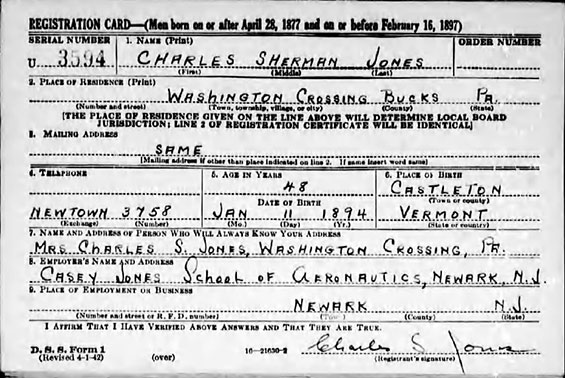

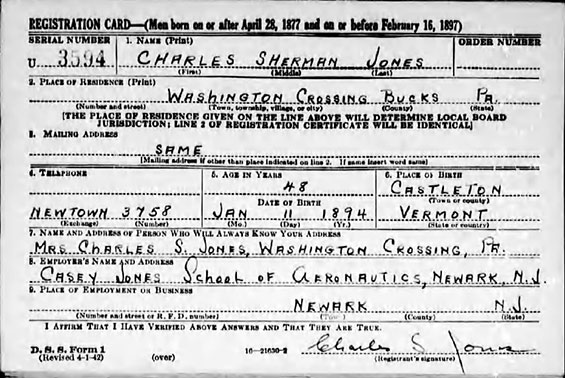

As with most men during WWII, Jones was required to register for the draft, even at his advanced age of 48. His draft registration card is below. On the reverse of the card we learn that he was 5'9", 155 pounds, with brown eyes and gray hair. The card was dated August 29, 1942.

Casey Jones WWII Draft Registration, August 29, 1942 (Source: Woodling)

|

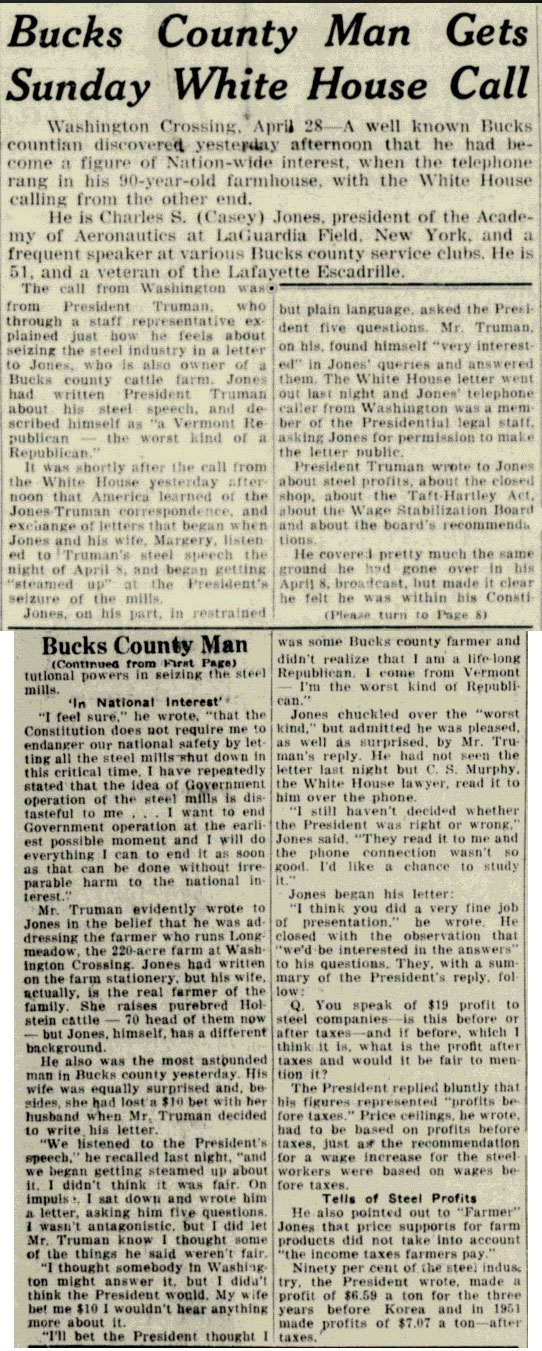

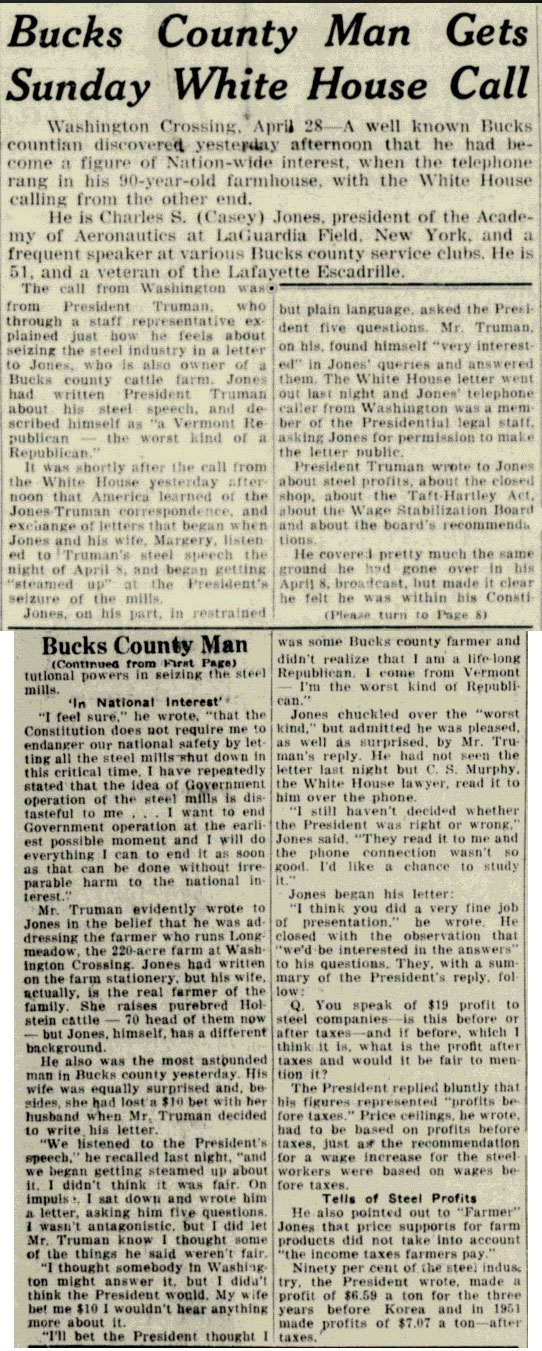

While living in Pennsylvania, Jones and his wife had a correspondence with then president Harry S. Truman. The substance of the correspondence, shared with us by Guest Editor Bob Woodling, dealt with a radio speech given by Mr. Truman regarding the federalization of steel companies. Through mutual agreement, Truman made their correspondence public by publishing the White House response to Jones' letter. An unsourced 1942 newspaper described their correspondence, below.

Unsourced Report of Jones-Truman Correspondence, April 1952 (Source: Woodlilng)

|

---o0o---

The (long), considered and courteous response by president Truman follows.

April 27, 1952

Dear Mr. Jones:

I have your letter concerning my radio address on the steel situation and I was very interested in the questions you raised. I wish I could take the time to write to the many hundreds of people who have written me about the steel situation. The majority of the letters I have received indicated approval of the action I took. From the letters indicating disapproval, it is quite apparent that many of the writers based their disagreement on a misunderstanding of the facts. Unfortunately, in the limited radio time I had, I could not possibly go into detail on all phases of the steel case. But I am going to take the time now to answer the specific questions in your letter.

The first question you raised relates to steel company profits. The profits figures which I used in my radio address were profits before taxes.

There has been a lot of discussion of this, but it should be clear that if you are going to establish fair price ceilings, you have to figure on the basis of income before taxes. If you took income after taxes, you would have to raise price ceilings to compensate for income tax increases. And if we let prices--and wages--go up to compensate for bigger income taxes, we would obviously not be preventing inflation, we would be encouraging it.

This is the reason we have to use profits before taxes in determining whether an industry is entitled to a price increase. It is the same with all other groups in the economy. The wage increases recommended by the Wage Stabilization Board for the steelworkers were based on wages before taxes-not on take-home pay after tax deductions. In adjusting wage rates to the cost of living, which is the practice in many industries, the standard used is the Consumers Price Index-which does not take account of the increased income taxes paid by workers. In determining fair price supports for farm products, the law does not take into account the income taxes that farmers pay.

Obviously, if we are going to be fair, business must be governed by the same stabilization principles applicable to wage earners, salaried persons and farmers.

It is true that the steel companies are paying high taxes. So is everybody else. If we allowed the steel companies to get price increases to cover their higher taxes, we would simply be shifting the tax burden to those less able to afford it.

As a matter of fact, the steel companies are making so much money that even with today's high taxes their profits after taxes are greater now than the profits they made after taxes in the three years before the Korean outbreak--and those were very profitable years. The Iron and Steel Institute has reported that its members--some 90% of the industry--averaged 494 million dollars in profits after taxes for the three years before Korea. That comes to about $6.59 per ton. And for 1951, the Institute reports profits after taxes of 668 million dollars--or $7.07 per ton.

So you see that whether you take profits before or after taxes, the conclusion is still the same. We will never be able to prevent profiteering in this emergency if we give the steel industry special treatment and immunity from the price control rules.

Second, you ask whether the "closed shop" was involved in this case. The "closed shop" is not an issue in this case, but the "union shop" is. I can understand your confusion on this point. The closed shop and the union shop are actually quite different. However, the two are commonly confused, and this confusion has been deliberately exploited in the propaganda of the steel industry. The dosed shop, which requires a person to belong to a union before he can be hired by an employer, is forbidden by Federal law. However, the Taft-Hartley Act specifically authorizes the union shop, under which employers and unions make an agreement requiring that workers become union members after they have been hired. There are many variations of such agreements. It is not uncommon to excuse old employees from joining the union, or even to allow a person to drop out of the union after the first year if he chooses.

The union shop was definitely an issue in this case. The Wage Stabilization Board felt that the issue was important enough to require a recommendation. The dispute obviously could not have been settled if this issue were not settled. It should be noted that the Board did not recommend any particular form of union shop. It recommended that the parties negotiate the form of union shop to be adopted.

Incidentally, the union shop is not new to the steel industry. Twenty-seven steel companies already have some kind of union shop arrangements in effect and some of the leading steel companies--including the United States Steel Corporation--which are objecting to signing union shop contracts with the steelworkers, already have union shop contracts with other workers they, employ.

Third, you asked about the Taft-Hartley Act. A work stoppage would have occurred December 31, if the union had not acceded to the Government's request to postpone strike action so that the Wage Stabilization Board could hear the dispute and recommend a fair settlement. By this means strike action was delayed, before April 8, for 99 days--voluntarily--whereas the Taft-Hartley Act could have delayed it only 80 days--by compulsion. I don't think it makes sense to use force when you can get cooperation by free consent.

After the Board made its recommendations, late in March, the parties resumed negotiations and Government negotiators on the scene were hopeful of settlement right up to the evening of April 8. A resort to the Taft-Hartley machinery during the time the parties were meeting, of course, would have stopped negotiations and destroyed any chance of settlement.

If I had used the Taft-Hartley Act April 8, there inevitably would have been a work stoppage--because under the Taft-Hartley Act, there is an elaborate procedure which must be observed before an injunction can be sought. A Board of Inquiry must be appointed, must hold hearings, and must prepare a report to the President. Only then may the President instruct the Attorney General to seek an injunction. All this takes time. On previous occasions, when I have used the Taft-Hartley Act, it has taken on the average from a week to days from the time a Board of Inquiry is appointed until the time the Attorney General may get an injunction. The Taft-Hartley Act simply would not have prevented a shutdown of essential steel production in this case.

Your fourth question is whether the public members of the Wage Stabilization Board were appointed on the recommendation [of] labor. They were not. The public members of the Board were appointed to their positions because they were experienced and qualified men to represent the public interest. Most of them have a firsthand familiarity with labor-management relations. As a matter of fact, their acceptability to both industry and labor is evidenced by the fact that several of them have frequently served as arbitrators of industrial disputes. In such situations, the arbitrator is the choice of both the union and the management, and his compensation is paid for jointly by the parties.

Those who seek to discredit the Board by charges that the public members are "prolabor" don't know what they are talking about. You may be interested to know that the National Advisory Board on Mobilization policy--composed of outstanding leaders from industry, labor, agriculture, and the public--reported to me only this week that they had considered this matter and unanimously found "the attacks on the integrity of the public members of the Wage Stabilization Board to be unfair and unsubstantiated by fact."

Finally, you ask whether the recommendations of the Board exceeded the demands of the union. They were in fact substantially less than what the union wanted. There were over a hundred issues in this dispute. On many of the union demands, the Board declined to take action or recommended that they be withdrawn. On others, the Board recommended that the parties settle for much less than the union asked for. This is only natural. The parties to a labor dispute rarely get all they want or feel they should have. Neither the union nor the steel companies could expect to be satisfied with the recommendations which would, all things considered, be fair to both parties.

I hope this letter will give you a better understanding of the steel controversy. I know the American people will make the proper judgment if only they get all the facts and see the issues. Your Government is doing all in its power to get the facts to the people. The officials of the Government are laying out the essential facts on wages and on prices before a number of Congressional committees. I can only hope that the newspapers of the country will give as much attention to those facts as they do to the paid political ads of the steel companies.

I realized that the action I was taking in this case was very drastic, and I did it only as a matter of necessity to meet an extreme emergency. In so doing, I believe that I was acting within the powers of the President under the Constitution--and indeed, that it was the duty of the President under the Constitution to act to preserve the safety of the Nation. The powers of the President are derived from the Constitution, and they are limited, of course, by the provisions of the Constitution, particularly those that protect the rights of individuals. The legal problems that arise from these facts are now being examined in the courts, as is proper, but I feel sure that the Constitution does not require me to endanger our national safety by letting all the steel mills shut down in this critical time.

I have repeatedly stated that the idea of Government operation of the steel mills is distasteful to me. I have twice sent messages to the Congress asking it to prescribe a course to be followed to achieve a solution of this case, if the Congress disagreed with the action I was taking. The Congress has not done so.

I want to end Government operation at the earliest possible moment, and I will do everything I can to end it as soon as that can be done without irreparable harm to the national interest.

I am taking the liberty of making my letter to you public in the hope that the information will be helpful to others who are equally anxious to know the real facts in this controversy.

Very sincerely yours,

HARRY S. TRUMAN

[Mr. C. S. Jones, Washington Crossing, Pennsylvania]

NOTE: Charles S. (Casey) Jones, president of the Academy of Aeronautics at La Guardia Airport in New York City, was a World War I aviator and a pioneer in the aeronautics industry. He maintained a 220-acre cattle farm at Washington Crossing, Pa. Mr. Jones's letter was chosen as representative of the body of mail expressing disapproval of the President's radio address on the steel situation (Item 82), and his permission was obtained to make the questions public along with the President's reply.

The findings of the National Advisory Board on Mobilization Policy on the situation in the steel industry were released by the White House on April 23. See also Items 82, 83, 103. |

| |

Provided courtesy of The American Presidency Project. John Woolley and Gerhard Peters. University of California, Santa Barbara.

|

|

After Casey Jones retired from Pennsylvania tdo St. Thomas, he flew West February 2, 1976, age 82.

---o0o---

THIS PAGE UPLOADED: 03/09/10 REVISED: 04/16/11, 08/27/11, 10/01/11, 01/14/18, 01/16/18

|

.jpg)