|

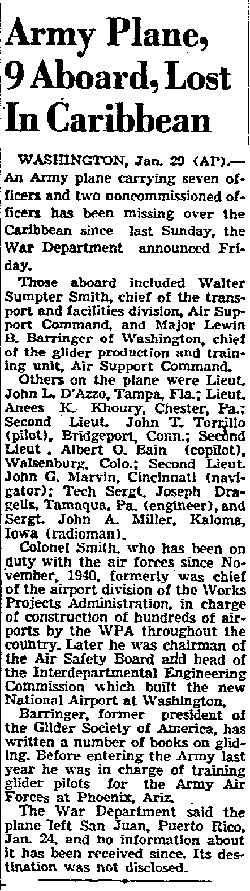

HE IS RESPONSIBLE FOR THE WIDE NETWORK OF U.S. AIRPORTS

AND HE BUILT WASHINGTON NATIONAL AIRPORT

Aviation Magazine, August 8, 1938 (Source: Woodling)

|

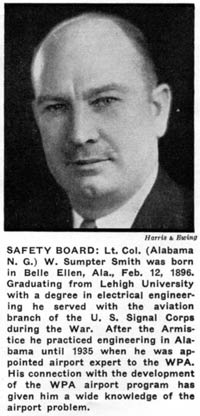

Sumpter Smith was born February 12, 1896 at Belle Ellen, AL and educated as an electrical engineer and pilot. He served as a flight instructor during WWI. Portrait, right from a 1938 article in Aviation Magazine, alludes to his career as a designer and builder of airports outlined below.

On August 22, 1917 Smith enlisted as a flying cadet. He was graduated from the Georgia School of Technology ground school and from the Park Field (St. Louis, MO) Primary Flight Training School. He was commissioned on April 4, 1918 as a pursuit pilot.

He was assigned to active duty at Park Field, Love Field (Dallas, TX), Call Field (Wichita Falls, TX), Wilbur Wright Field, (Dayton, OH), Gerstner Field (Lake Charles, LA) and Rockwell Field (San Diego, CA) where he completed his pursuit training. The was then assigned to Ream Field (San Ysidro, CA) where he served as flight instructor in advanced pursuit, combat, aerobatics and gunnery.

Sumpter Smith, Ca. 1918 (Source: Smith Family)

|

While at Ream Field, according to this link to a family-produced Web page, he participated with other Army pilots to form a stunt squad that performed aerobatics over San Diego, CA during the WWI armistice, ca. November 11, 1918. The vignette, left, is from an annotated group photo of the stunt squad posted on right hand side of that page (q.v). Interestingly, the pilots in that photo are, L-R, Haskell Bass, Smith as shown, Dudley Watkins, Jimmy Doolittle and Bill Williams. Besides Smith and Doolittle, Watkins also signed the Davis-Monthan Register: a hat trick! Another photograph from around the same time of Doolittle and four other aviators is at the link. I is difficult to say if the men in this photo are the same ones as on the Smith family link; they are wearing leather helmets which cover some of their features.

Contributor Woodling (cited, right sidebar) shares the following description of the photograph, "The five daring acrobats whose daring skill provided the chief thrill of the day were Lieutenants D. W. Watkins, H. H. Bass, J. H. Doolittle, W. S. Smith, and H. O. Williams, all of Ream Field, who won the right to form the stunt squad in

open competition from a score of the pilots."

Smith landed twice at Tucson. His first visit was Tuesday, October 15, 1929 at 11:00AM. Based at Roberts Field, AL, he arrived carrying Col. U.N. James in the Curtiss O-11 Falcon he identified as 27-1 (this particular airplane was eventually converted to an O-11A). They were west bound from El Paso, TX, Ft. Bliss to San Diego, CA, Rockwell Field.

According to inferences made from the family Web page linked above, Smith was part of a flight of two O-11s. His wingman was John M. "Snake" Donalson who signed the Register just below Smith. Donalson carried as passenger "Capt. H. Smith," who was Sumpter Smith's brother, Hester. At the Smith family's Web page you can read that "Hes" was the navigator of Donalson's ship, and that the purpose of their flight was to attend the National Guard convention at Long Beach, CA. The assumption is that Hes and his brother were attending the same convention, because Sumpter noted his point of origin for his second landing as Long Beach.

Sumpter Smith's second visit was five days later on Sunday, October 20, 1929. He carried the same passenger in the same airplane. As mentioned, they were eastbound from Long Beach, CA, but they did not cite a destination or departure time. Neither did they cite a purpose for their flight, but we know it was to attend National Guard activities at Long Beach, and their destination was back at Roberts Field, AL. Sumpter, a major when we see him at Tucson, was commissioned Lt. Colonel August 12, 1932.

Donalson and Hester did not sign the Register during their return trip. From the family's Web page, we learn the reason why, as follows, "Their time was limited, so on Sunday, they [Donalson & H. Smith] began the long flight back to Alabama.

"Everything went well until nightfall, and it was pitch black. They were supposedly over a new airport [location unspecified], but couldn't see it or find it, as they circled in the night sky. The Curtiss was out of gas and running on fumes, and a discussion ensued where they decided that they would have to bail out, rather than crash land, as the airplane had that tendency to burn.

"At the very last moment, below them, lights came on, and they could see the runway. The pilot immediately dove towards the runway, and landed.

"They found out that the airport had closed for the day, and a janitor was cleaning up. He heard the airplane circling overhead, realized the pilot could not find the airport. Almost unheard of, runway lights were not a common accessory for airports of that day. Luckily, this airport had just installed them, and the janitor knew where the light switch was!

"The next day, they refueled and continued on to Birmingham, arriving back home on Monday without further incident. Hes said that the day they got home, the stock market crashed, ushering in the Great Depression!"

Hester Smith was the navigator on the flight because his eyesight was below the standards required for pilot ratings at the time. Below, an undated photograph of Hester (L) with two unidentified officers and an unidentified woman. Hester wears eyeglasses.

Hester Smith (L), Date & Location Unknown (Source: Smith Family)

.jpg) |

Sumpter Smith followed what might be called a non-standard career path. Instead of progression up the officer ladder with command assignments of increasing responsibility, he went to work in government programs that were at the time invoked to ameliorate the conditions brought on by the Great Depression. He served first as chief liaison officer, then Director, of the Work Projects Administration (W.P.A.), Division of Airways and Airports. The Division operated from 1935-1942.

An interesting route to understanding the evolution of Smith's career is to look at Roberts Field in Birmingham, AL, Smith's home base. As background, Smith was appointed to the Alabama National Guard during September, 1921 and commissioned as a 1st lieutenant (he remained an officer in the National Guard until his call to active duty in 1940, see below). During what follows, Smith also maintained registration as a Professional Engineer in the State of Alabama (#384), and a current civil Transport Pilot license (T-4844).

Roberts Field had its beginnings in 1919, when a group of eleven WWI flyers formed a club named the "Birmingham Escadrille." Their aim was to promote aviation in Birmingham and the State of Alabama. Lobbying by the club convinced the War Department to establish an air National Guard unit, the 135th Observation Squadron, at Birmingham in 1922. Smith was detailed to assist in organizing the Squadron.

The organization grew to 26 officers and 120 enlisted men and the 135th changed its name to the 106th Observation Squadron on January 1, 1924. Smith was commanding the 106th Observation Squadron at Roberts Field in 1929 when he visited Tucson. Among his duties at Roberts was good samaritan work for the surrounding areas of Alabama. For example, under his command in 1929, the Squadron served the State when almost the entire Squadron was ordered to active duty for flood relief in south Alabama. Twenty-five officers and 100 men participated for 14 days and nights, flying approximately 300 hours dropping food and medicine to marooned families . The airdrop of supplies was among the first of its kind in aviation history (see Register pilot Charles Howard for another, later, example).

By 1930, the facilities at Roberts Field were long in the tooth, but the 106th did not have the funds to move or improve. A steady campaign of publicity and pressure on legislative and local government was maintained until it was decided to build new facilities for the Squadron at the Birmingham Municipal Airport as part of a government works project in 1934. About that time, after advocating for the Squadron, Smith was moved to the 31st Division of the Alabama National Guard. It is not clear if he kept his hand in the Roberts Field development project while serving with the 31st.

However, it took nearly four years to complete the construction of the new home of the 106th at the Birmingham Municipal Airport, but in 1938 the Squadron was finally able to move into its new quarters . Eventually, the base was named after Sumpter Smith, lending testimony to his role in its development and construction.

Given his experience with the the politics and planning of military construction projects, in 1935, as mentioned above, Smith was made Director of the Airways & Airports Division of the W.P.A. In that capacity, he was responsible for the improvement, design and construction of a nationwide network of more than 600 airports. On the coattails of that assignment, he was later appointed chairman of the Safety Board of the Civil Aeronautics Authority (C.A.A.). Coincident with his appointment, he was also assigned in an advisory capacity to serve on a C.A.A. board formed to investigate the accident of the Hawaii Clipper piloted by fellow Register pilot Leo Terletzky.

Illustrating his role is the article, below, from the Seattle (WA) Daily Times for Saturday, October 23, 1937. Here Smith shows up with other Air Commerce and W.P.A. officials at Seattle and Portland to evaluate and support the construction of new airport facilities at Portland. Smith is at right in this poor-quality photograph. The banner headline that ran this day read, "W.P.A. TO SPEED PORTLAND AIRPORT WORK."

Seattle (WA) Daily Times, Saturday, October 23, 1937 (Source: Woodling)

|

The Safety Board was another matter. The problem was that he was filling two roles. He chaired the Safety Board and led the National Airport project. Politics prevailed, as indicated in the next couple of unsourced news articles. As background, there were three members of the Board; Smith as chair, C.B. Allen and Tom Hardin. First, from Tuesday, May 7, 1940.

CIVIL AERONAUTICS ROW

The president had a secret conference with congressional leaders the other day over reorganization

of the Civil Aeronautics Authority, at which he told them that one big reason for reorganization was to end a fierce, disruptive feud inside the Air Safety Board. This autonomous agency is the focal point of

the fight over CAA. Roosevelt's opponents claim that if the Air Safety Board is robbed of its independence, the safety of air transportation will suffer.

But according to Roosevelt, this is exactly what will happen unless the Air Safety Board is forcibly revamped. He told the congressmen that the internal war among the three members had reached such a pitch as to impair the agency's effectiveness. The president's story of the ASB ruckus was as follows: Trouble started when Sumpter Smith, then chairman, became ill In February, 1939, and C. B. Allen, a former New York aviation writer, was appointed to a vacancy on the Air Safely Board. Within a few weeks, Allen teamed up with the third member, Tom Hardin, vice president of the Airline Pilots Association" (AFL) and these two virtually took over the agency.

They set about reorganizing the board's administrative machinery and firing friends of Sumpter Smith. Smith fought back, but Allen and Hardin held an election, deposed Smith as chairman and put Hardin in his place. Smith rushed to the White House with the cry that the election was illegal. Then his two

rivals accused him of violating the Civil Aeronautics Act by holding the chairmanship of the government committee supervising construction of the Capital's new airport. Smith indignantly denied this, saying he had an official ruling permitting him to hold the additional post.

Firing back, Allen and Hardin asserted that Smith had not agreed with them in one single report on a major, airplane accident, so that every report made by the ASB was a split opinion. Smith countered that this wasn't his fault, but his opponents'; they should have agreed with him.

The feud finally reached such a stage that Hardin and Allen refused to permit Smith to look at the transcript from which the board's minutes are compiled, because they said he had a secret understanding with the stenographer to take down their off-the-record remarks.

The president also told the congressional leaders that the Air Safety Board repeatedly has clashed with the Civil Aeronautics Authority and was at loggerheads with the aviation industry. "For the sake of efficiency and for the best interests of the industry," he said in effect, "it is absolutely necessary that this situation be cleaned up. It can't be allowed to go on. This personal feud has completely demoralized the Air Safety Board.'

|

Some things never change. Next, from Friday, May 24, 1940.

WASHINGTON—The department of commerce is on the spot. It was put there by 46 senators, who voted for President Roosevelt's reorganization plan No. IV and threw the independent Civil Aeronautics Authority back into the department. The situation was this: Two years ago, after more than three years of wrangling, investigating and lobbying, the McCarrin-Lea bill knocked out the

Bureau of Air Commerce (then in the commerce department) and set up the independent CAA. Although it is not generally known, this really was one of Jimmy Roosevelt's babies when he was secretary to his father.

The CAA was made up of a five-man board, whose duties consisted principally of establishing rules, regulations and standards; an administrator in charge of the physical set-up of the bureaus of

federal airways, safety regulation, private flying and certificate inspection; and the three-man air safety board, charged independently with investigating all accidents, determining their cause and reporting to the CAA board for action.

On March 29, 1940, less than two years after this new agency started functioning, the commercial

airlines established the comparatively amazing record of flying 87,300,000 miles, carrying more than

2.000,000 passengers, -without a single fatal accident.

HIT HOUSE FIRST

On April 11, while the bouquets still were showering down, the president tossed his little bombshell:

Reorganization Plan No. IV, which abolishes the air safety board entirely, and puts the CAA back into

the commerce department. Under the law, unless BOTH houses of congress vetoed the plan within

60 days, it was to become effective. The hullabaloo that this order raised almost knocked the dome off the capitol. The scrap, for weeks, shared editorial honors with the war in Europe. The house of representatives, where such critical downpours are felt (especially in election year) hastened to vote on the order and opposed it by the healthy vote of 232 to 153.

The senate, aware of the seriousness of the matter, took two days out to debate it, even after the long hearings in committee. It was in the heat of these arguments, coupled with the vote that upheld the order, that the department of commerce was put on the spot. Dire things have been predicted for aviation. It's charged that the order is a kickback to the days when the infant transportation industry was a political football with human lives the stake. Let one fatal accident occur in commercial aviation after June 11, when the new order becomes effective, and there'll be an investigation from here to Borneo.

GUESSING GAME

What actually was behind the order is another of those capital mysteries that may never be solved.

The president said simply that it was to effect economy, more adequate supervision, and eliminate friction that now exists in CAA. C. B. Allen, former New York newspaperman, and Tom Hardin, ace pilot, will lose their jobs when the safety board is abolished (Sumpter Smith, other member, already had resigned to become director of the national airport). Allen has his own private explanation for the order. "My mother," says Allen, "always was very proud of me. Everytime I took a step up the ladder or achieved some little success she'd say 'I knew it, son, you are going a long way.' But never in her wildest dreams did she ever think I would reach such heights that the president of the United States would burn a house down just to get me out of it."

|

Below, from the Library of Congress (LOC), Sumpter Smith (L) and his nemesis, Tom Hardin after their assignments to the Safety Board on August 22, 1938. At least they're not pointing fingers at each other, yet.

Sumpter Smith (L) and Tom Hardin, August 22, 1938 (Source: LOC via Woodling)

|

Indeed, Smith had been asked by President Roosevelt to resign his position with the Civil Aeronautics Authority in order to devote full-time as chairman (as well as engineering projects officer) on the commission to build Washington National Airport. The New York Times of November 22, 1939, below, left, documented his resignation. The ceremonial ground breaking for Washington National was on November 21, 1938. Further, president Roosevelt split authority into two agencies in 1940, the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) and the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB). CAA was responsible for Air Traffic Control, airman and aircraft certification, safety enforcement, and airway development. CAB was entrusted with safety rulemaking, accident investigation, and economic regulation of the airlines. Both organizations were part of the Department of Commerce. Unlike CAA, however, CAB functioned independently of the Secretary of Transportation.

Smith Resignation, The New York Times, November 22, 193(9?) (Source: NASM)

|

January 29, 1943, Unsourced News Article (Source: Woodling)

|

Regardless, his new assignment regarding the Washington National Airport was a sizeable project with far-reaching responsibilities. For example, the commission was authorized to pass on all job items as to plans, specifications, estimates, materials, equipment and execution. It would review all proposed contracts, make general decisions on engineering and construction methods and materials and refer to the Civil Aeronautics Authority all matters needing its decision as sponsor of the project.

Below, Smith ponders an architect's drawing/model of the airport terminal.

Sumpter Smith and a Model of the Washington National Airport, December 2, 1939 (Source: LOC via Woodling)

|

The photo above illustrates Smith's additional responsibility to coordinate with the U.S. Treasury Department's public buildings division for the preparation of designs for the buildings, and with the procurement division for preparation of specifications for advertising building contract bids. The Army Corps of Engineers was allotted $600,000 for dredging operations, which began and continued through that winter, 1939-40. On September 28, 1940, two years to the day of the site selection, President Roosevelt laid the cornerstone of the terminal building at the dedication ceremony.

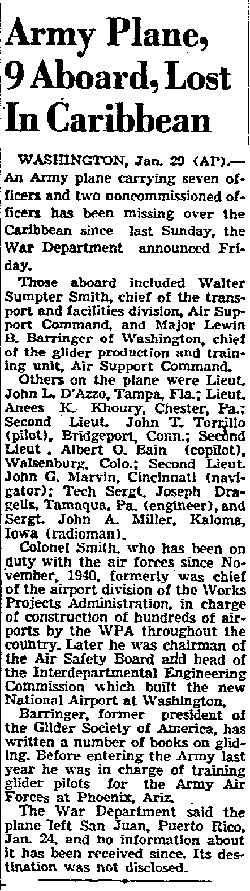

With the approach of WWII, Smith was recalled for active duty as an air officer in the 31st Division. He was promoted to full colonel in 1942. On January 24, 1943 Smith's aircraft disappeared over the Caribbean Sea enroute to satisfy some unknown role to support the aftermath of the Casablanca Conference (held January 14 to 24, 1943).

Smith's role might be divined from his title at the time. He was Chief of the Transport and Facilities Division, Directorate of Ar Support, Headquarters of the Army Air Forces. We could easily see him involved with air support, airfield construction and logistics for the invasions of Sicily and Italy which, along with the demand for unconditional surrender by the Axis Powers, were settled at the Conference.

The article, above, right, states that he was lost in the Caribbean. However, headed for Africa, his airplane could have landed anywhere enroute, which included South America and the Atlantic Ocean. Note the lack of mention, for obvious reasons, of the type of aircraft, the specialties of the other officers on board, or their destination. It doesn't even suggest they were headed for Africa. It is not clear from the article whether Smith was flying the airplane.

In October, 1943 Smith was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Medal. The citation read in part, "For exceptionally meritorious service in the performance of duties of great responsibility from March 9, 1942 to January 24, 1943." During that period he had supervised construction of 90 air-support bases in vicinities near camps of more than 10,000 men. The award went on to read, "By his untiring efforts, excellent judgement and comprehensive knowledge, these bases were completed in record time."

Ironically, his organization that had provided him with so much challenge during the last half of the 1930s, the W.P.A., was disbanded on June 30, 1943, six months after his disappearance. It was a result of high employment due to the economic boom of World War II. He was inducted into the Alabama Aviation Hall of Fame in 1984.

---o0o---

Dossier 2.2.164

THIS PAGE UPLOADED: 04/22/12 REVISED:

|

.jpg)