|

THE SOUTHERN ROUTE

Take a look at a US map that shows terrain features and you'll

see that the east-west line defined by El Paso, Tucson, Yuma

and San Diego follows relatively low elevations. This, along

with fuel capacity and altitude limitations of early aircraft

designs, is a big factor in why the Davis-Monthan Airfield

was a popular stopping place for civil, military and commercial pilots traveling east from California and west from New York during the Golden Age of flight.

CHRONOLOGY OF THE DAVIS- MONTHAN AIRFIELD

Early Tucson airports occupied a couple

of different geographical sites around the city in the 1920's.

The identity and timeline of changes for the several fields is described in the references in the lower left sidebar.

We are interested in what became the Davis-Monthan Airfield. The genealogy is fairly straight-forward. In 1919 the City of Tucson allocated a property south of city center. The field was at its position on what would become the corner of Livingston Ave. and S. 6th St. in south Tucson. It was what was called the Tucson Rodeo Grounds.

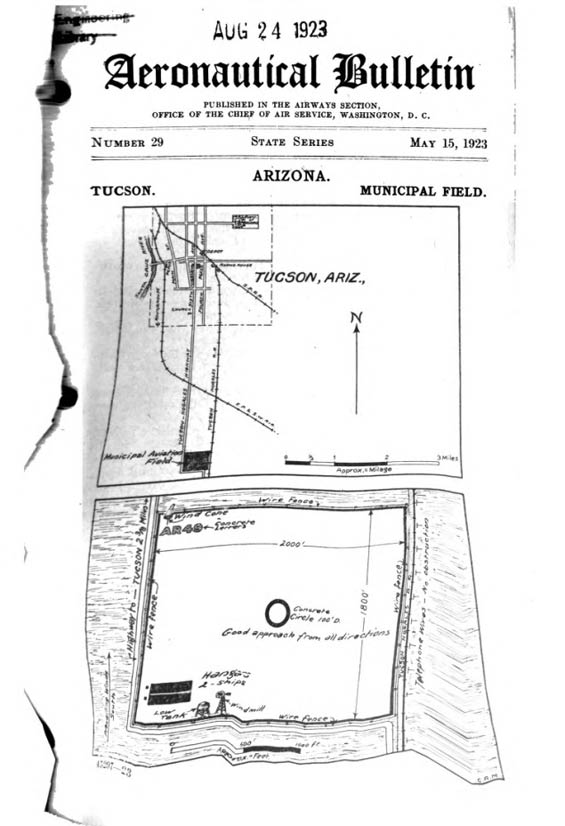

The earliest official diagram I have is below, dated 1923, courtesy of a site visitor. The property was called the Municipal Field. The hangar building shown in the lower left corner of this diagram is still standing today.

Tucson Airport Diagram, May 15, 1923 (Source: Site Visitor)

|

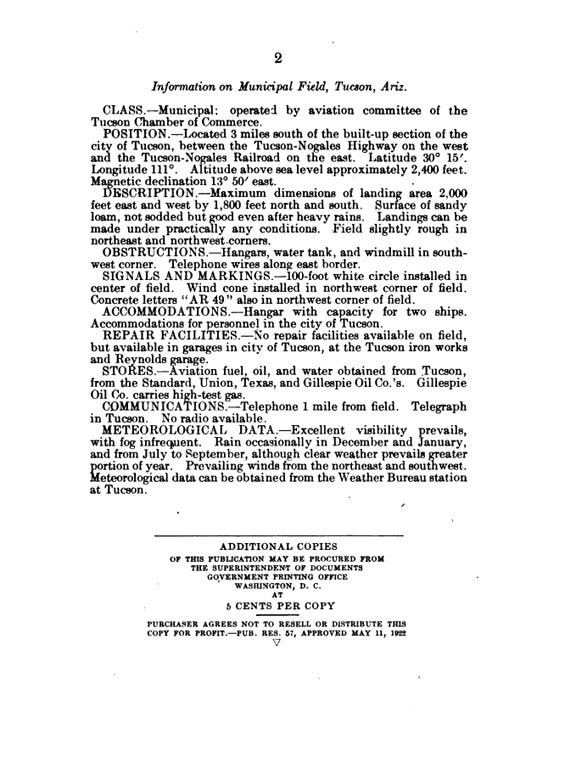

The warped nature of the diagram is due to a scanning anomaly at the source. Note that this location is a square. Compare it to the asymmetric quadrilateral of the later, ca. 1927, location shown in the aerial photographs just below. Immediately below, the text description from the Aeronautical Bulletin for May 15, 1923, which accompanied the diagram above.

Tucson Airport Description, May 15, 1923 (Source: Site Visitor)

|

Late in 1926, the airfield was moved farther south to its present position. The location of the "new" Davis-Monthan Airfield is currently in the northwest

corner of the Davis-Monthan Air Force Base (refer

to the series of images below).

At right is an early image

of the airfield in its present location, probably before 1932,

facing southwest. The present Davis-Monthan Air Force Base

is toward the upper left and off the photo (image from DMAFB

Office of Natural/Cultural Resources).

If you study the definitive history linked at left, you'll discover on page 17 of that document that the "new" location was completed in 1927, just in time for its dedication by Charles Lindbergh during his visit at Tucson in September that year.

Apropos the Davis-Monthan Airfield Register, it lay open at both the "old" Municipal Field and "new" Davis-Monthan locations. When it was moved to the new location can be inferred, plus or minus a few months, from information on the biography page for pilot Al Gilhousen. Although the actual date is not clear, it was near February 6, 1927. Not only does the scrap of paper exhibited at Gilhousen's page state, "First plane to land on new Davis-Monthan Aviation Field," but an article in the Tucson Citizen of February 7, 1927 states the same, "The first ship to land on the new Davis-Monthan field,..., set down to a perfect three-point landing by Al Gilhousen, commercial pilot, carrying passengers Sergt. Dewey Simpson and Paul Gustine." Additional images of the Airfield are available on this site at the Cosgrove Photograph and Document Collection.

Below, left, is an image of the airfield in

1936, just before the register record ends. North is toward

the top of the image (both images courtesy of DMAFB Office

of Natural/Cultural Resources). I added the property lines

and dates.

At right is an identical image from 1954. Notice

the changed geometries of runways and taxiways, some extending

and following the same path as the old runway. Look closely

and you'll see changes were also made to some of the buildings

on the southwest border of the airfield. The Air Force Base property clearly extends south and east of the old airfield property boundary.

In the aerial photo of the airfield above, left,

the square, southernmost building, directly above the "9",

is the Army Air Corps hangar built in 1932 by the WPA. It

is a utilitarian, well-built structure, with sliding doors

on the north and south sides, and a glass block facade on

the northwest. This page (PDF 626KB), from the "Western Flyer" in 1931 tells

of the plans and funding for the hangar (it also mentions

other airfields near Tucson).

DETAILS OF BUILDINGS ON THE AIRFIELD

IN THE 1930s

The image at left is cut from the image directly

above it. It specifically identifies some of the structures

on the field (courtesy of Mr. Thomas). At top is the location

of staff homes. Al

Hudgin, the FBO manager, and Dewey Simpson, the Airfield

manager, rented homes (labeled "staff homes") on the west side of South Alvernon Way.

The American Airlines terminal, welcoming the

Douglas sleepers and many movie stars, was located on the

west border. The location of that building is now under some

50 feet of elevated roadway.

The approximate location of the Lindy Light

(see newspaper references, right column) is shown, although

there is conjecture as to its exact location. The "cottage"

was allegedly the home of Dewey Simpson. However, Mr. Thomas

and his resources agree that Mr. Simpson did not live in the

cottage by the AAC hangar. See this link to the Cosgrove Photograph and Document Collection for ground level images of these structures that clarify their juxtaposition.

The nighttime image at right (taken in 1928),

from the Arizona Daily Star in 1956, is of the large quonset-type

hangar owned by the City of Tucson. Around the mid-30s, Al

Hudgin rented this hangar and started his own business

of aircraft maintenance and flight instruction. It was out

of this hangar that Alan Thomas took his first airplane ride

in a bright red Stinson, and then learned to fly with Mr.

Hudgin as his instructor.

The final building is the Gilpin hangar. Before

you read on, please link to C.W.

Gilpin for some background on this building. This is the

hangar built at the Airfield by ..... This image was taken

after the building was moved to...

STILL WORKING ON THIS SECTION....

I HAVE AN IMAGE OF THE American Airlines TERMINAL

COMING ALSO...

1932 HANGAR TODAY

The 1932 hangar stands today as we speak, and

it is the subject of a move to make it a National Historic

Landmark. We should all wish that endeavor well, not only

for the obvious historic importance of the building, but also

for the impact the people and airplanes that visited the Airfield

made on the future of aviation.

The photo,left, of the southeastern face of

the terminal, was taken in 2002. The wind was blowing on the

day I took that photo. As it jostled and blew through the

sliding hangar doors I could hear the sighs, gossip and whispers

of a thousand pilot ghosts passing through the cracks, each

recounting their flights long ago, and requesting their stories

be told.

The concrete pad visible in the foreground was

the floor of Al Hudgin's hangar SE of the terminal in the

1936 and 1954 photos.

At right is your Webmaster at the glass block

NE facade and entrance door of the 1932 hangar. Of the pilots

and passengers you call from the dropdown menus, above, who landed

after 1932, many passed through this door. As a pilot, standing

there was powerful juju. You will understand this better as

you further explore this Web site.

Left, above, inside the terminal you see the

robust structure of the ceiling, with old-style slant out

windows painted over, and porcelainized light reflectors.

According to Mr. Thomas, Dewey Simpson, the airfield manager,

stored extra wings for the Boeing P-26 in those rafters. That

airplane was prone to ground loops and when it happened he

always had a spare wing to mount.

Below, today the space is being used for Air

Force Base storage, including what looks like a vertical stabilizer

from an A-10 at center.

To the right, a view of the 1932 hangar looking northwesterly.

The old runway, a later asphalt version (ca. 1937), is visible as a faint

line running left to right at the lower half of this photo.

The original checkerboard roof pattern has been replaced with

text identifying Davis-Monthan Air Force Base active units.

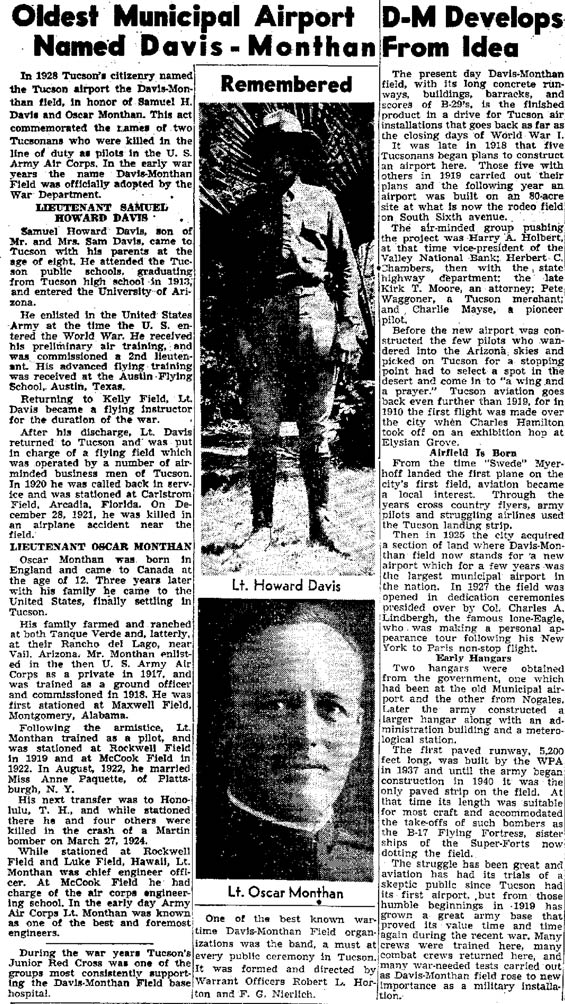

Below is a news article from theTucson Daily Citizen of August 1, 1947. In the wake of the end of WWII, the history of the Airfield was summarized in this article. Thanks to Guest Editor Bob Woodling for sharing this article.

Tucson Daily Citizen, August 1, 1947 (Source: Woodling)

|

Davis was killed flying the Curtiss JN-6HG-1

"Jenny" AS#44796. In the same newspaper, the advertisment below features the Pioneer Hotel. The hotel was a common resting place for Register pilots and passengers.

Tucson Daily Citizen, August 1, 1947 (Source: Woodling)

|

Below, a baggage label from the Pioneer Hotel.

Pioneer Hotel, Baggage Label, Date Unknown (Source: Cosgrove)

|

GOLDEN AGE TRAFFIC AT THE AIRFIELD

Interesting is the report of traffic numbers cited by Reinhold

(p. 97ff. in the reference top left column). For 1926, Reinhold

reports 215 landings, with 185 landings made by military aircraft.

The Register database (queried by year) yields 210 total landings,

with 185 made by military pilots. Traffic for other years

cited by Reinhold is more or less in agreement with the Register

and my database derived there from.

Regardless of the minor discrepancies, on average, by today's

standards, airfield traffic was "relaxed". In the

register, which lay for pilots to sign on a desk at the field

between February 6, 1925 and November 26, 1936, we count 3,704

landings. This is just about one logged landing per day over

the life of the register. But, when you go through the list

of pilots and airplanes, quality certainly outshines quantity!

The graph of counts below (I know, it needs updating), extracted

from my database, shows that traffic was by no means evenly

distributed, especially for 1928 and 1929, just before the

Great Depression.

It is clear, after Lindbergh dedicated the field in 1927

(see this link),

traffic increased over three times annually. Unfortunately,

aviation ran into the Great Depression and from 1929 on traffic

dropped to about one airplane per week in the mid to late

30's. Maybe this is why the Register record stopped in 1936.

A slight majority of landings each year was made by military

pilots. The Depression had about the same effect on civilian

and military aviation alike.

THE DAVIS-MONTHAN AIRFIELD TODAY

Below are two aerial photographs I took during 2002 as I was vectored

toward Tucson International Airport for landing. I have outlined

very roughly the location of the original airfield as it is

positioned in the northwest corner of the Davis-Monthan Air

Force Base. Photo below from the northeast with the runways

of Tucson International (TUS) labeled in the background.

An Overlay of the 1927 Site (Source: Webmaster, 2002)

|

At right, closer in, looking southwest past the leading edge of my

left wing. The 1932 hangar building is visible as the white

structure on the property line. The concrete pad of the Hudgin

hangar is visible just to the left of it. A faint shadow of

the original runway can be seen in the lower right quadrant

of the image (not the taxiways, but a really faint shadow

that runs through the apex of the two taxiways).

Finally, I offer a treat, below, of the approach plate used

during the 1940s for the AN range let down at the Davis Monthan

Air Force Base. I leave the image writ large so you can enjoy

the similarities between this early notation and our contemporary

approach plates. Some things change; some things remain the

same. Image courtesy of Alan Thomas.

RECENT PRESS COVERAGE FOR THE AIRFIELD

The following is quoted from the Tucson Citizen

of Tuesday, December 16, 2003 (from part II of a three-part

series written by C.T. Revere).

"....There was a time when Tucson's military presence

was a one-man outfit.

In 1925, two years before Davis-Monthan Airfield came to

be, the U.S. Air Service dispatched Army Staff Sgt. Dewey

Simpson to Tucson to set up a refueling station for transcontinental

flights that landed at the remote desert outpost.

Simpson's one-man post was set up at the Tucson Municipal

Flying Field, now the Tucson Rodeo Grounds.

His first customer, Simpson told the Tucson Daily Citizen,

was Jimmy Doolittle, who later led a U.S. bombing raid on

Tokyo in response to the attack on Pearl Harbor [Note: the

first signature in the Register is that of Al Gilhousen. Perhaps

Doolittle visited first, but did not sign the Register]..

Two years later, Simpson's refueling station was moved to

the city's municipal airport, which was renamed Davis-Monthan

Field in honor of pilots Samuel Davis and Oscar Monthan, both

Tucsonans who died in plane crashes after World War I.

The dedication ceremony Sept. 23, 1927, was a day of hoopla

and celebration featuring a visit by America's most famous

flier, Charles

Lindbergh, just four months after he became the first

pilot to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean.

An estimated crowd of 20,000 people - nearly the entire population

of Tucson - turned out to greet the aviation hero and see

him throw the switch on a large rotating beacon called the

"Lindy Light."

Davis-Monthan and Tucson continued to grow at a sluggish

pace through the late 1920s and into the Depression.

In 1930, the city was home to 32,506 people, and D-M featured

a crew of three men. A weather and radio station for the post

was still a year away from construction.

Ten years later, Tucson was home to 37,763 and America still

a distant observer of the war in Europe. Davis-Monthan, with

a crew of 25 enlisted men, was designated an Army Air Base

in 1941.

After the United States was drawn into World War II, Davis-Monthan

became a training station for medium-range bombers and was

equipped with B-18s and B-25s.

As the war progressed, the focus on the base shifted to training

crews for heavy bombers and D-M eventually trained nearly

20,000 crew members for B-24 "Liberator" bombers.

By 1944, the B-24s were replaced by B-29 "Superfortress"

bombers, with crews trained at D-M.

After the war ended, the newly created Air Force chose D-M

as home for the 4105th Army Air Force Unit, which was charged

with storage and maintenance for military aircraft left over

from the war.

The storage facility, now called the Aerospace Maintenance

and Regeneration Center, is home to more than 4,200 military

aircraft, some of which are ready for use and others used

for spare parts.

During the years since World War II, D-M has been a training

site for pilots and crews of numerous aircraft, including

the F-86A "Sabre," and the A-7 "Corsair II."

In 1976, D-M became the training base for the A-10 "Thunderbolt

II," which showed its meddle in the Persian Gulf War

and more recently in Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation

Iraqi Freedom.

In 1980, another plane common in the Tucson skies joined

the complement at D-M - the EC-130 "Hercules."

The giant cargo plane is now used as a flying battlefield

command post and for jamming enemy communications. It also

is used in support of D-M's newest addition, the Combat Air

Rescue Group, along with HH-60 Pave Hawk helicopters.

David Taylor, a city planning administrator, said Tucson

would be a very different place without Davis-Monthan.

"If we had been bypassed by the Great War's training

effort, it's totally hypothetical, but I think we would be

a fraction of our current size," he said.

"We would not have grown a lot between the turn of the

century and the 1940s and I don't know what would have driven

our growth in the years after World War II."" |

August 30, 2017 The following article appeared in the Tucson Daily Star, August 19, 2017. The article celebrated the 242nd anniversary of Tucson, as documented in a new book by William Kalt III titled "High in Desert Skies: Early Arizona Aviation."

A half-dozen years after the Wright brothers’ first flights in late 1903, the first fearless aviator arrived in the Old Pueblo. Pioneer stunt flyer Charles K. Hamilton thrilled an excited crowd with his machine and airborne stunts, taking off from a makeshift landing field near where the Tucson Convention Center sits today.

“Come to Tucson and See the Man-Bird Fly” promised an advertisement for $1 tickets to the Feb. 19, 1910, Aviation Meet. The event brought the city streets to life thanks to organizers businessmen Mose and Emanuel Drachman and Chamber of Commerce president George F. Kitt, whose family names still hold a place in Tucson. Locals, cowboys, miners and other visitors clustered around Elysian Grove recreation park at the foot of Simpson and Cushing streets.

Each of Hamilton’s ascents ended in calamity. On the first day, a pesky wind current ripped one of the silk wings on his aeroplane (as they were first called). He slammed into the Grove’s newly installed posts for greyhound racing the next day, but he succeeded in flying 3 miles and reaching 700 feet in altitude.

Although Tucson’s event came quickly on the heels of the nation’s first major show in Los Angeles the previous month and Arizona’s first in Phoenix days before, it was a financial disaster since many watched outside the designated area without paying. Over the next two decades, though, Tucson entertained a host of aviators and established a reputation as a pilot friendly city.

As we celebrate Tucson’s 242nd birthday (Aug. 20, 1775) Sunday, William D. Kalt III’s new history of early Arizona aviation, “High in Desert Skies: Early Arizona Aviation,” provides a look at the major developments in an important aspect of our past. He dives deep into the aircraft, personalities and events around the world as aviation took hold. With the focus on Arizona, the book also includes tales of Phoenix and the namesake of Luke Air Force Base, the community of Douglas and Nogales hero Ralph A. O’Neill.

Follow along as Kalt introduces some of these big events and major players.

‘Flying School Girl’ impresses Old Pueblo

After Charles K. Hamilton’s show, it was 1915 before another aerial show came to Tucson. That November, America’s “Flying School Girl,” Katherine Stinson, awed fans at Pima County’s Southern Arizona Fairgrounds. The role of women in early aviation proved significant and, as the Arizona Republican newspaper observed, “It seems to be quite clear that women do not intend to be content with remaining on the earth during the dawn of the great new era of the air.”

Katherine’s brilliant smile, gentle grace and superb flying skills endeared her to Tucsonans during her performance. She shared the fine points of her loop-the-loop trick and carried the city’s first official mail delivery.

Historic airport hosts Army aircraft

The next airplanes to fly into Arizona arrived in December 1918, much to the exhilaration of the town’s aviation boosters. With word that a squadron of Army aircraft would arrive in just three days, city leaders scrambled to locate and clear an airfield. East of present-day Evergreen Cemetery along North Oracle Road, the new landing grounds greeted aviators with great frequency following its groundbreaking.

Unsatisfied with the landing strip, however, city leaders pressed for a permanent airport. Mayor Olva C. Parker and Councilman Randolph E. Fishburn led the push and the city established the nation’s first municipally owned airport in the summer of 1919. Located at South Sixth Avenue and Irvington Road, now the Rodeo Grounds, the airfield provided safe haven for incoming airmen and Tucson earned a sterling reputation among flyers.

World Cruisers put Tucson on the map

Hamstrung by the public’s lingering fear of flying, hampered by its remote Southwestern location and blocked by governmental torpidity, Tucson’s airport remained without an airplane hangar when the beacon of national glory shined upon it in 1924.

As the Army’s Douglas World Cruisers returned to the United States on the first around-the-world flight, wear on their engines forced the squadron’s commander, Lowell H. Smith, to alter his flight path and come through Tucson rather than scale the Rocky Mountains on the way to the West Coast. The town of just more than 20,000 relished their visit, which placed it on the map with Paris, Budapest, Strasbourg and others. Kirke T. Moore, dubbed Tucson’s “Daddy of Aviation,” greeted the airmen and six Arizona cities presented them with Navajo blankets at an opulent welcome banquet.

Local visionaries help expand airport

During their 1924 visit the Douglas World Cruiser flyers advised Moore that the city airfield’s runway stood too short for landing their larger planes and the lack of a hangar and mechanical help made the local operation unattractive.

Pima County Engineer John “Mos” Ruthrauff joined Moore and aviation enthusiast Birtsal W. Jones in driving the city’s purchase of 1,280 acres. This airport’s hangar remains today east of Alvernon Way and Golf Links Road and on the edge of Davis-Monthan Air Force base.

How Davis-Monthan received its name

Three of Tucson’s airfields have been designated Davis-Monthan, two municipal fields and today’s Air Force Base. In 1925, the city named the airport at the current Rodeo Grounds in honor of two local pilots who died in airplane crashes: Samuel Howard Davis, a Tucson High School graduate and horseman, and Oscar Monthan (pronounced Mon-tan), a member of a Vail ranching family and one of the Army’s best and foremost engineers.

While little is known of the Davis family to date, Monthan family members remain in the area. Among them is 95-year-old, George R. Monthan, Oscar Monthan’s nephew, who carried on the family’s aerial legacy by piloting fighter planes off aircraft carriers as a career naval aviator.

Lucky Lindy makes glorious landing

With its new airfield already serving airplanes, Tucson marked its early aviation pinnacle when Charles A. Lindbergh arrived in September 1927. Accorded international adulation for the world’s first solo trans-Atlantic flight, he followed his grand achievement with a tour of the United States in the Spirit of St. Louis aircraft.

Six-year-old George Monthan stood with his parents at the local airport on the day America’s flying wonder landed.

“I got to climb around the Spirit of St. Louis,” he recalls. “My dad lifted me up and I looked in the cockpit. Lindbergh was my first real close exposure to flying. When I was old enough, if I saw a group of airplanes landing, I’d jump on my bicycle and race south down Alvernon Way to see them at the airfield.”

Col. Lindbergh’s sole Arizona stop drew an estimated 20,000 spectators to the University of Arizona campus and local florist Hal Burns presented him with the “Spirit of Tucson,” an almost life-size airplane made of cactus. Lindy officially dedicated the new airport Davis-Monthan at the evening’s sumptuous banquet.

After the city moved its municipal airport to its present location in the early 1940s, the military kept and enlarged the airfield, today’s Davis-Monthan Air Force Base. In 1948, the Tucson Airport Authority revived a floundering municipal operation and helped build it into the Tucson International Airport, which now serves more than 3 million passengers annually.

|

---o0o---

THIS PAGE UPLOADED: 04/29/05 REVISED: 12/08/05, 01/23/06, 09/23/12, 05/29/13, 01/08/14, 08/30/17

|